This content was published: May 17, 2020. Phone numbers, email addresses, and other information may have changed.

Hieronymus Bosch on Heaven and Hell

Gabe Blackburn

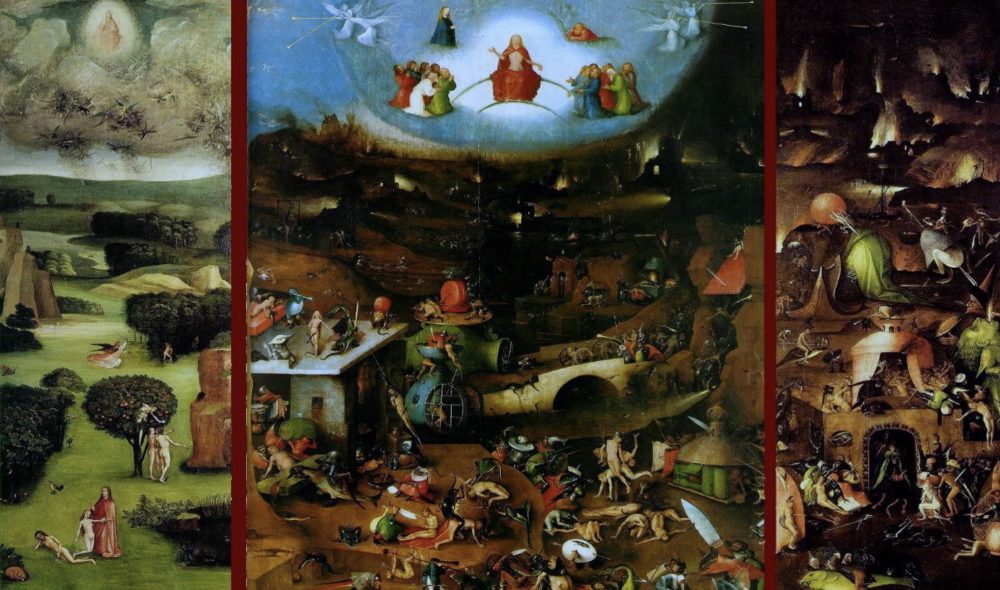

Hieronymus Bosch was a painter in the Netherlands during the Renaissance often attributed with influencing many modern depictions of Hell. A typical painting of Hell from Bosch usually consisted of houses molded from flesh, continued torture of the inhabitants, and hellfire pouring over the landscape. Despite his obvious fascination with the interpretation of Hell, he did not dismiss the idea of Heaven altogether. Several paintings use angels, God, Jesus, and Heaven; even his most well known work of art, The Garden of Earthly Delights, contains a beautiful world inhabited by Adam and Eve, alongside God himself. While researching the life of Bosch may not result in pages of stories similar to other well documented painters during the Renaissance period, his creations speak for his ideals, whether they contain humans lusting for and indulging themselves in a life of pleasure, or those same people being punished violently for what he saw as a life of sin.

The mid-fifteenth century marked an important leap for religious reformation when individuals began to become more independent of churches, and had more freedom to create their own faith without strict guidelines. Nathan Dunne summarizes, in “How Hieronymus Bosch’s Hell Lives on Today,” the shift that caused many artists, especially Bosch, to make such a drastic change in how they viewed religious scenes: “His birth coincided with the Age of Discovery, when Western Europe began its global mapping of the world, and Christianity was undergoing a movement that anticipated the Protestant Reformation […] these earlier reforms called for making the Christian life one’s own, rather than relying on the church’s strict interpretations.” During this period, as Dunne mentions, the Bible was no longer the one true and righteous exposition for Christians to follow. Practicing religion became more about one’s self, and less about the church. For art, this meant a shift away from repetitive paintings of Christ hanging from a cross, to a much more strange and wondrous time where ideas were challenged and imagination ran wild within religious interpretations. Dunne explains how Bosch took this newfound freedom and put his mind to work through painting the terrifying underworld and all the devices he believed came with it: “Bosch saw hell as a physical world eternally separated from God. The idea was to render hell as a place so unthinkably foul that people would fear God.” This was achieved by turning Hell from a static, fiery realm of damnation, into an entire plane where war constantly raged  between under equipped souls, and the abominations that lurked within the ominous nightmare. One such painting, simply titled Hell, builds upon previous implications of Hell by using a river, not unlike the Styx from Greek mythology, as a sanctuary for the demons, and a painful constriction for the damned. The evil beings that plague the land latch onto sinners and do as they please, whether that means slicing them up, or dragging them away to be served an unknown, but certainly unpleasant, fate.

between under equipped souls, and the abominations that lurked within the ominous nightmare. One such painting, simply titled Hell, builds upon previous implications of Hell by using a river, not unlike the Styx from Greek mythology, as a sanctuary for the demons, and a painful constriction for the damned. The evil beings that plague the land latch onto sinners and do as they please, whether that means slicing them up, or dragging them away to be served an unknown, but certainly unpleasant, fate.

Comparing this to what Bosch was painting just five years earlier demonstrates the dramatic shift in ideas perfectly. Crucifixion With a Donor exhibits Jesus Christ nailed to a cross alongside holy figures beneath him. Color remains vibrant in this world with the fields stretching from the foreground to the village in the background, surrounded by beautiful forestation. Jesus has died for the sins of mankind, opening a world of hope through repentance. Various bones lay scattered around the cross, potentially hinting at the dark turn Bosch would take in future endeavors; yet this painting simply rehashes a famous religious event without taking any real risks. Meanwhile, Hell is an early showcase of the fiendish spirits who perform Satan’s biddings no matter how grotesque. This land is inhospitable, exemplified by the dead trees unable to produce oxygen, to the smoke adorned sky allowing only enough light to spot silhouettes to seep through. Scavenger birds watch with glee as their next meal is prepared in front of them by the natives through gruesome acts of murder. The drab color palette drains any aspiration brought from the overworld, and any comprehension of basic anatomy is mixed between two realities while viewing hellspawn next to their human victims. This painting challenges preconceived notions about the last place anyone would want to end up in the afterlife. Hell was a largely unexplored world when it came to artistic vision, typically portrayed as a world of fire with the only antagonist being a variation on the devil; Bosch made sure to expand upon previous ideas by taking advantage of the newly introduced reimagining of religious concepts in ways that had not yet been created. This painting may seem quite tame compared to other, more dense paintings from Bosch, but it epitomizes the change in religious imagery many artists would begin to adopt during this time period.

While being famous for his grotesque images of Hell, Bosch also spoke at great lengths about how someone would end up serving their limitless sentence through his colorful depictions of a variety of holy religious imagery. Creations attributed to Bosch also often told a story through multiple panels, usually forming a triptych. The Garden of Earthly Delights, both one of his earliest and most well known works, tells a story beginning with Adam and Eve, presumably being introduced by God, followed by a large burst in the population causing hundreds of humans to run amok, naked and lustful, and finally, those same souls being condemned to a life of eternal damnation to pay for the sins committed in their previous life. The world illustrated before the population boom appears peaceful and teeming with wildlife. The animal kingdom consists of horses drinking from the river, giraffes roaming the open fields, and predators consuming their freshly hunted prey. Humans soon disrupt the serenity that Bosch created when they begin their path towards a life of indulging in their deepest, lustful desires with no boundaries between them. The animals are quickly treated as tools to ride, torment, and kill as their world is taken over by an ever growing abundance of humans that seek only to please themselves. To pay for their deformation and deviance upon a peaceful land, the offenders sink to a world unknown, where an entirely new life of punishment awaits.

Bosch manages to use each panel in the triptych to tell life stories: Adam and Eve, the lives of the sinners decimating Earth and breaking sinful boundaries, and finally their eternal discipline following previous actions. Obviously, this is not quite the story the Bible told, and this painting could very well be seen as secular, as Lynn Jacobs points out in “The Triptychs of Hieronymus Bosch,” despite the various holy themes appearing throughout the triptych: “The Garden of Earthly Delights also has significant secular content within its central panel: whether interpreted as a scene of sin or of the paradisiacal state of man before the Fall, the center focuses on earthly pleasures” (1016). There is no doubt that Jacobs’ note on the absence of holy figures is true; however, the inclusion of a Biblical story, alongside a new interpretation of Hell more than proves that this image is meant to be religious from beginning to end. Besides animal abuse, people are partaking in sexual activities involving many others, with very little care to the surrounding area. Explicit acts of intercourse are on display, including extremely strange scenes such as someone being sodomized by a flower, once again destroying nature around the area. Plenty of figures are seen touching the breasts or crotches of their peers, and disturbingly, a few cases look forced. Finally, Mother Nature herself is violated, whether it is by bringing fish onto land, working animals beyond their limits, or disrespecting local flora with inappropriate uses. These blissfully unaware perpetrators would all be met with fate when they are forcefully taken hostage within an unsettling abyss, harnessing unpredictable horrors and sentences matching their sins. Bosch was definitely no stranger to the Bible, and portrayed what he believed to be the ultimate sins within his envisioned lands before Hell.

Bosch manages to use each panel in the triptych to tell life stories: Adam and Eve, the lives of the sinners decimating Earth and breaking sinful boundaries, and finally their eternal discipline following previous actions. Obviously, this is not quite the story the Bible told, and this painting could very well be seen as secular, as Lynn Jacobs points out in “The Triptychs of Hieronymus Bosch,” despite the various holy themes appearing throughout the triptych: “The Garden of Earthly Delights also has significant secular content within its central panel: whether interpreted as a scene of sin or of the paradisiacal state of man before the Fall, the center focuses on earthly pleasures” (1016). There is no doubt that Jacobs’ note on the absence of holy figures is true; however, the inclusion of a Biblical story, alongside a new interpretation of Hell more than proves that this image is meant to be religious from beginning to end. Besides animal abuse, people are partaking in sexual activities involving many others, with very little care to the surrounding area. Explicit acts of intercourse are on display, including extremely strange scenes such as someone being sodomized by a flower, once again destroying nature around the area. Plenty of figures are seen touching the breasts or crotches of their peers, and disturbingly, a few cases look forced. Finally, Mother Nature herself is violated, whether it is by bringing fish onto land, working animals beyond their limits, or disrespecting local flora with inappropriate uses. These blissfully unaware perpetrators would all be met with fate when they are forcefully taken hostage within an unsettling abyss, harnessing unpredictable horrors and sentences matching their sins. Bosch was definitely no stranger to the Bible, and portrayed what he believed to be the ultimate sins within his envisioned lands before Hell.

There is no doubt that Hell has exerted a deep influence on human culture for many lifetimes. Bosch’s ideas for how the realm of the damned would appear through the eyes of the living is seldomly forgotten when any interpretation of Hell arises. Sarah Dias examines the use of imagination that helped Bosch mold scenes of Hell previously unexplored by other artists: “His work was completely derived from a combination of his own imagination and the Biblical stories that inspired him. This way of making work was revolutionary at the time and Bosch was the first artist attributed with creating scenes, which were all together new, mined in part from the unconscious.” She reinforces that Bosch was truly the first to interpret Hell the same way modern depictions portray it through various uses such as in popular culture. Most of the subjects within his work partake in sexually charged activities, which was often considered by more religious individuals as a turn from blind obedience towards God, to a life of remorseful disobedience, an act that, in the eyes of Bosch, was punishable by eternal torture in Hell. His famous triptych, The Last Judgement, depicts a Hellscape where fire does little besides complement the background. The foreground consists of dead bodies being strung up as if they were on display, others being impaled on weapons, and the unlucky inhabitants being raped and tortured by the creatures native to this foreign land. This painting interpreted from left to right once again begins with Adam and Eve, but soon focuses much more on the punishment they passed down to many generations through their act of lust.

Despite the drastic change in scenery between the first and following panels, the colors within the triptych remain largely untouched. All three backgrounds fade into darkness, while the foreground contains both greens and browns. However, the abundance of green and brown are switched between the overworld and the underworld, with green the primary color above ground, and brown taking over below, perhaps signifying that the underground is a much darker and dirtier place to be cast towards. Hell’s newcomers are greeted by frightening atrocities that simply should not exist: large heads carried only by feet, multiple animal-human hybrids, inanimate objects with human features protruding to create living beings, all lie within the ranks alongside stereotypical demons with horned heads accompanied by clawed hands. God watches over the underworld, seemingly with little care despite his guests looking towards him with absolute horror. Perhaps in this scenario, God believes the punishment is fair considering the types of activities that took place outside of Hell. Once again, scenes contain sodomy using strange objects, only this time the objects are more akin to flagpoles, rather than flowers. The common act of touching exposed areas of the body returns, but now the dwellers inside the cavern are forcing themselves upon the humans, and unlike above ground, no one is enjoying it. Finally, Mother Nature is completely absent in the depths beneath, and the only people being brutalized and killed this time around are the humans themselves. This depiction of hell is an image mirrored from the overworld to the underworld where every sin committed against others is now committed against the offenders. The work Bosch put towards making Hell the most undesirable outcome would be a new standard set for many generations to come.

Bosch created a previously unthinkable world where anyone who breaks a religious vow would be sent to a realm that reeks of death and contains perpetual cries of agony. Unfortunately, he left very little documentation of his own life behind, leaving the true intentions behind many of his works lost to time. However, considering the time he was alive and the themes upon which he based his work, the idea that he lived his life as a devout man of religion, wanting to serve a purpose to God is almost certain. He achieved this by making a life of sin seem quite uneventful compared to what awaited sinners below their world of constant debauchery.

Works Cited

- Bosch, Hieronymus. Crucifixion With a Donor. 1485, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. Bosch, Hieronymus. Hell. 1490, Palazzo Ducale, Italy.

Bosch, Hieronymus. The Garden of Earthly Delights. 1490-1510, Museo del Prado, Madrid. Bosch, Hieronymus. The Last Judgement. 1482, Academy of Fine Arts, Austria. - Dias, Sarrah Frances. “Hieronymus Bosch Artist Overview and Analysis”. TheArtStory.org 15 Jan. 2018, theartstory.org/artist/bosch-hieronymus/.

- Dunne, Nathan. “How Hieronymus Bosch’s Vision of Hell Lives on Today.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 27 Apr. 2016, theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/201 6/04/how-hieronymus-boschs-hell-lives-on-today/479409/.

- Jacobs, Lynn F. “The Triptychs of Hieronymus Bosch.” The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 31, no. 4, 2000, pp. 1009–1041.

Gabe Blackburn is a PCC Sylvania student working towards a transfer degree in business. His goal is to eventually become a CPA one day. Music has always been his biggest inspiration. An avid concert-goer, he has recently started practicing guitar, and surprisingly, taken up a bit of singing. However, his vocal skills, or lack thereof, will remain reserved for his ears only. This essay was written for a Writing 122 course taught by Patrick Walters at Sylvania Campus. For the assignment, students were asked to work with still images, whether paintings or photographs. They were also tasked with finding and integrating secondary sources.