Autism and Disability Stigmas

Hosted by Amanda Antell. Produced by the Let's Talk! Podcast Collective. Audio editing and transcription by Carrie Cantrell & Chrispy Jones. Web Copy by Nic Meza Honea. Webhosting by Eugene Holden. Visual editing by Ryan Vail and Erik Wideman.

Out of the Ashes – An Autistic Journey to Wholeness

Story by Nic Meza Honea, Edited by Carrie Cantrell, Ash DeHart

High-functioning autism, formerly known as Asperger, can often be misunderstood by people who don’t experience it. Today, we understand autism as existing on a spectrum of behaviors and neurological experiences. These experiences can include having hyper-interests, engaging in soothing repetitive behaviors known as stimming, and communicating through diverse means. In this episode of Let’s Talk: Autism, our host Amanda Antell interviews Ash DeHart on how they present themselves to society and the many struggles and harmful stereotypes that society puts onto people living on the spectrum.

“I did not have familial support around my neurodivergency, and back then, I don’t even think people really understood what autism was.”

Living with autism can be complicated, made even more so by the lack of a familial or community support network. For Ash, who is a multi-racial adoptee, growing up in their family meant dealing with stigmas, stereotypes, and tokenism early on. Ash muses,

“Adoption can sometimes commodify children because parents who adopt feel like they may have paid a price for having a particular experience as a parent instead of being a safe and loving place for a child who needs a home. And that’s narcissism.”

They recall an expectation to perform normatively in their early family life and suppress a lot of their natural neurodivergent behaviors. They sought acceptance as many do on the autism spectrum by mimicking neurotypical behaviors and leaning into the stereotypes of their at-birth gender assignment–overt sexuality and femininity, a fun & entertaining “party girl” personality, and a downplayed intellectualism despite their incredible intelligence.

“But through therapy, and through building my self-esteem, and being rooted in my own personhood, and being able to come out as non-binary, I am no longer afraid to hide the dark past. Because the dark past is one of the best assets I have to help another human being that may be sick or suffering, be they autistic, neurodivergent, or non neurodivergent. And so today, I’m grateful for the experiences that I’ve had, no matter how hard they are, and I’m not ashamed to stand up anymore and be Ash.”

Today, Ash has been clean for almost ten years, but their journey to self-awareness and self-acceptance took them through cycles of addiction and abuse. Ash’s time in the music industry forced them to engage with sexual harassment and assault, rape, character assassination, and regular substance abuse. Ultimately leaving the toxic environment to begin a healthier life path, Ash now understands:

“..it’s okay for me just to be me the way that I exist. I’m not damaged. I’m not bad. I’m not broken. I was just born with a different kind of brain and a different kind of mind.”

After a near-brush with self-harm, Ash has found solidarity in their community and their mental health care team. Now leading the musical project “Dead Letter Era,” Ash practices holistic living after emerging from their dark past. Living alone is common for people who are autistic because it provides an opportunity to create self-accommodation in so many ways around diet, mobility, environment, and rest. Ash is a light socializer, focusing on balancing studies, work in advocacy, and time in nature.

“I spend a lot of time in nature, too, and I feel as though as a society, we become disconnected from nature because most of us live in these gargantuan cities surrounded by concrete and walls and noise. And after a certain amount of time, if we don’t step out into nature and reconnect with that energy and that spirit that nature gives, we can become very depressed, sad, ad infinitum.”

Ash encourages anyone–on the spectrum or neurotypical–to embrace their true self despite ableist standards. There are networks of people and resources that can support you on your journey.

“…if you’re feeling overwhelmed, and that you can’t do this anymore, there is help out there, there are people that care, there are people that understand this as neurodivergence. Reach out. Get the help.”

Resources

- Suicide prevention hotline – Dial 988

- National Domestic Violence Hotline 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE) TTY: 1-800-787-3224

- Call To Safety (formerly the Portland Women’s Crisis Line) 1-888-235-5333 Local: 503-235-5333

- RAINN – National Sexual Assault Hotline 1-800-656-4673 (HOPE)

- PCC Counseling – Counseling services, crisis support, and more resources.

- PCC Accessible Education and Disability Resources – Get accommodations, support, and network with the disabled community.

Let’s Talk: Autism

“Autism and Disability Stigmas”

This week, Amanda is joined by Ashes as they discuss the labels and stereotypes placed on them by others while growing up and living with Autism.

Hosted by: Amanda Antell

Guest Speaker: Ashes

Produced By: Let’s Talk! Podcast Collective

Released on: 2/2/24

Autism and Disability Stigmas Transcript

Transcripts edited by Carrie Cantrell

Pre-show Introduction and Disclaimer

Chrispy Jones: You’re listening to Let’s Talk! Let’s Talk! is a digital space for students at PCC experiencing disabilities to share their perspectives, ideas, and worldviews in an inclusive and accessible environment. The views and opinions expressed in this program are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Portland Community College, PCC Foundation, or XRAY.FM

We broadcast biweekly on our home website, pcc.edu/dca, on Spotify, and XRAY 91.1 FM and 107.1 FM.

Introduction

Amanda Antell: Hello and welcome to today’s episode of Let’s Talk Autism. I am the host and producer of this series, Amanda, and we are covering the topic of disability stigmas. I was joined today by Ash, who bravely shared their story on how the various stigmas they faced in their childhood shaped their adult life.

Sharing experiences today was truly an amazing experience as this topic evolved into a story of genuine survivorship and how life can become better even after the darkest of periods. This episode will contain mentions of childhood sexual abuse, exploitation, and domestic violence, so this content may be triggering to some audience members.

With that in mind, please enjoy the conversation.

Ash DeHart: Hi, my name is Ash. My pronouns are they/them. I am a student at Portland Community College. I study history and political philosophy, and I’m planning on transferring to study to be a human rights attorney, focusing on marginalized populations and state overreach.

I also work as an Accessible education and disability resources advocate and I hopefully will be working soon at the Clear Law Clinic helping houseless clients expunge their criminal records.

CLEAR Clinic is a free legal clinic at PCC Cascade in North Portland. They provide free legal services to Oregonians. Source: Logo provided by CLEAR Clinic. You can find more information at this link or by clicking the image: https://www.pcc.edu/legal-resource-center/

Oh yeah, and I am diagnosed with high-functioning autism, formerly Asperger’s syndrome. I forgot to add that in the beginning, so I’ll add it now.

Question 1

Amanda Antell: So, how would you describe your diagnostic journey in terms of your autism?

Would you say that you were diagnosed early in life, later in life, and how did your diagnosis come about?

Ash DeHart: I was actually diagnosed as an adult, as a young adult, because I did not have familial support around my neurodivergency. And back then, I don’t even think people really understood what autism was.

People just knew I was really, really, really smart, but that I was really different in a lot of ways, too. And so, the journey to answers, to put the pieces together, to understand how my brain works and how that manifests in my day-to-day life didn’t really start until I was older because I got diagnosed as a younger person, as a young adult, but I was busy doing so many things that really pursuing knowledge on what high functioning autism is didn’t come until I was in my 30s.

And so when I got older, I started doing the research and learning about the condition and how it affected me. And that was a super positive thing for me because I started to learn why I function the way that I do as opposed to how a non-neurodivergent person may function.

Amanda Antell: Thank you.

Ash DeHart: You’re welcome.

Amanda Antell: So for me, I have a similar story to you where I was diagnosed as an adult, But I was diagnosed at 31. I don’t know if anyone would consider that a young adult or not at this point, but I was diagnosed at 31 and my story is very typical of women my age and people races women my age because Back in the 90s, when I was a kid, It was thought that autism really only happened in boys.

And so, I was very different, and I presented a lot of signs of autism, but no one wanted to diagnose me. My mother tried desperately to get me diagnosed. She took me to three different experts, quote unquote. And these were like real therapists. It’s not like she found them out of the newspaper or something.

So, they all told her that I was just really smart but just didn’t learn in the classroom environment in a traditional way, and that just didn’t help her. So, what would happen is I’d be punished for a lot of behaviors that were natural to me but not natural to other people. And I was bullied very severely in middle school because of that.

And. It was only until I met my mother-in-law that she suggested I had autism, and that was the first time I even heard of autism, and I had been 16 at the time. I eventually did get diagnosed after my therapist suggested it much later in life, and that’s how I discovered I was autistic and just everything made sense, and I felt really happy because I finally felt like I got closure about my childhood and just why I was so different, and I felt like There’s nothing actually wrong with me.

My brain is just wired very differently.

Adoption and Tokenism

Ash DeHart: Exactly. To piggyback on what you were saying about your familial surroundings and the punishment, you know I wasn’t raised in my family of birth. I was adopted. And so, the people that raised me, they were very narcissistic in a lot of ways. And I think they adopted me just so they could parade it around to their wealthy friends.

Oh, look at the part Native American child that we adopted, et cetera, et cetera. To fluff their tail feathers in the community. But they were not nice people. And I was punished repeatedly for years and years and years and abused for simply just being who I was, and that damaged me deeply and it was only through years of therapy and ongoing therapy and counseling that I still participate in now that I have come to grips with the fact that what they did was wrong and unacceptable.

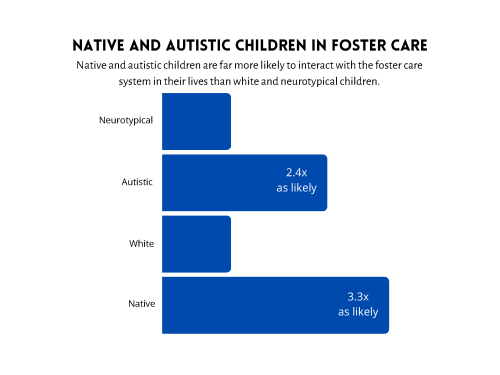

Figure by Ryan Vail: Native and autistic children are far more likely to interact with the foster care system in their lives than white and neurotypical children. The bar graph shows that autistic children are 2.4 times as likely and native children are 3.3 times as likely. Source: https://adoption.com/children-with-autism-more-likely-to-be-in-foster-care-new-research https://oregonvbc.org/foster-care/

And that it’s okay for me just to be me the way that I exist. I’m not damaged. I’m not bad. I’m not broken. I was just born with a different kind of brain and a different kind of mind.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, I had a narcissistic parent, too, so I kind of get what you’re saying. But before I go on, there’s always been something I’ve been super curious about, like, wealthy people who adopt people from different ethnic backgrounds from them.

What is with that? How is that a… why is that a status symbol for them?

Ash DeHart: There’s a lot of schools of thought on this, and I don’t really know what was going through their mind when they adopted me, obviously, because. I was a child, but it became popular in mainstream culture when celebrities like Angelina Jolie and others started adopting children of other races.

Of course, I was adopted long before all that, but I’m sure the seeds had already been sown in wealthy cultures as to where people would just run out and choose a child that was disadvantaged so they could contribute to the well-being of the child. But in general, adoption can sometimes commodify children because parents who adopt feel like they may have paid a price for having a particular experience as a parent instead of being a safe and loving place for a child who needs a home, and that’s narcissism and adopted children already deal with relinquishment trauma and our primal wound from initially being given away, even if we aren’t old enough to remember or verbalize it.

And so, to be in an adoptive household where you are essentially being told that you are unwanted or you’re being abused, it hurts us even more than it could other people. And I was constantly reminded about the situation that I was adopted from a biological mother who was a drug addict. And that I should be grateful for being adopted, and they regularly called me ungrateful when I wasn’t and something I realized after years of therapy is that you do not have to be grateful for being adopted, whether you are neurodivergent or non-neurodivergent, whether we are born into a family, given by the government or paid for. Being someone’s child is something for them to be grateful for, not the other way around.

Amanda Antell: Kind of going off that I would say that It’s the parent’s decision to bring a child into their family regardless if it’s birth or adoption And therefore, they’re responsible for providing for you, and quite frankly, the whole you should be grateful for what we give you, regardless of how we treat you, to me, that’s just like a really classic control maneuver.

I don’t think there’s anything else beyond that. At least, that’s how I’ve always looked at it from my narcissistic parent. It’s just a means of control to guilt you into submitting to them. So don’t fall for that b if you still ever have lingering doubts about that.

Ash DeHart: Exactly. And I know now today that the people who adopted me had their own issues, and they were incredibly damaged people.

And I should have never been given to them, but I will say this, in the state that I was adopted in, that I was brought to and adopted in, the woman that handled the adoption was my adoptive mother’s best friend, and she was head of the agency who legitimized the adoption. So, there was cronyism involved.

And it was from that cronyism that I suffered greatly at the hands of people who had no business raising children. But I don’t see myself as a victim anymore. I don’t hold that mentality. I am a survivor. Yes, I went through some horrific things. Because of those horrific things, I made some bad life choices in younger years.

I became addicted to drugs. I used to drink too much. But I’ve been clean for multiple years now. And I’ve built a really good life. And I use my survivorship as a way to continue to empower myself and to empower other autistic people and non-neurodivergent people in our local community.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, that’s incredible.

I think I’ve said that to you before too, where you’re a survivor, and I don’t think you have anything to be ashamed of regardless of what happened in your past. The fact that you’re here now telling your story that’s everything to be proud of.

Studies show children on the spectrum are up to three times as likely as their neurotypical peers to be targets of bullying and physical or sexual abuse. Source: Pixabay.

Ash DeHart: Thank you so much. This is a first step for me coming out and speaking publicly about being neurodivergent, about being abused, about being a former addict, about speaking to how I was raised, how it affected my life, and it’s super empowering for anyone.

Because we, as neurodivergent people, fear can have a huge stranglehold on us more so than it does with non-neurodivergent people. Because we already suffer a lot of the times with feeling like we don’t fit in, or we’re too different, or do people want me around? Am I doing okay? And then you put serious issues like this into the mix.

And the fear can become overwhelming. And for 15 years, I largely have kept silent about what transpired in my life, but through therapy and through building my self-esteem and being rooted in my own personhood and being able to come out as non-binary, I am no longer afraid to hide the dark past because the dark past is one of the best assets I have to help another human being that may be sick or suffering.

Be they autistic, neurodivergent, or non-neurodivergent. And so today, I’m grateful for the experiences that I’ve had no matter how hard they are. And I’m not ashamed to stand up anymore and be Ash.

Amanda Antell: And you are Ash. And to me, you have everything to be proud of. To me, everyone’s stories matter. Everyone’s experience is different. And they don’t invalidate each other. So, tell your story however you want, at the pace you want.

Ash DeHart: Thank you, Amanda.

Question 2

Amanda Antell: So, how would you describe your daily life as an autistic individual? What daily things overwhelm you or underwhelm you? And take up executive function. What sensory issues do you deal with? And I know that’s a lot in one question, so tackle that question however you want.

Ash DeHart: Well, in my daily life. I have a nice apartment near the river, downtown, in our lovely city.

I use certain forms of lighting because I can get very overstimulated with fluorescent lighting. I have my house arranged in a certain way that is accommodating for me, that has created a beautiful cocoon where I can go to school online and I can work. Being in a classroom and in an office environment 24/7 during the work week hours can be overwhelming for me. I don’t mind going into an office setting or a classroom every once in a while, but I’m one of those more solitary type autistic people who needs to spend a lot of time alone. I have to be really careful of my diet. There’s certain foods that I just can’t eat, namely gluten.

I’m also hardcore vegan. So, there’s dietary issues there that have to be addressed to keep everything running smoothly. I use a lot of hemp-based CBD products. To combat anxiety and autism spectrum things that go on in the brain, which is like super helpful. And I have to credit CBD was giving me wholeness in a way because it puts me on a platform where I can communicate better with people.

I used to suffer from severe, severe social anxiety disorder that got so bad at one point. I became agoraphobic for a couple of years, and I’m really glad that I overcame that because there’s a beautiful world out there to enjoy. I spend a lot of time in nature, too, and I feel as though, as a society, we become disconnected from nature because most of us live in these gargantuan cities surrounded by concrete and walls and noise, and after a certain amount of time, if we don’t step out into nature and reconnect with that energy and that spirit that nature gives, we can become very depressed, sad, and infinitum, and I often wonder if a lot of the blanket depression symptoms we’re seeing across the board in people are attributed to a lack of time in nature.

Other things I use to function in my day-to-day life I use the Otter app to help me retain information because I also have a traumatic brain injury on top of the high-functioning autism. So that makes my life a whole lot easier because I can refer to everything and have it in order, so I’m not confused and feeling frustrated.

Since I’ve moved back to Portland, I’ve noticed I have a hard time making friends here because the city is not the friendly place that it used to be when I lived here a long time ago. And I know you and I have talked about that. I really tried to come out of my comfort zone by trying to talk to people. I’ll be in the stacks at Powell’s or the library, and I’ll make a nice comment to someone, and sometimes people will speak, but most of the time, they just look at you, and they don’t say anything because we’ve just become a very isolated society because of the pandemic and from other factors too. I don’t judge because you never know where someone’s coming from in their own personal journey.

So, I’ve been trying to work towards learning how to build community more now that I’m back here in Portland, and I’m super grateful for my position at AEDR because it does allow me social interaction that I didn’t have before, and so it makes me really happy. And I’m going to be starting therapy with a local therapist who deals specifically with autism spectrum clients around issues I had with abuse in the music industry. I’m also a former semiprofessional musician. And so, I’m really excited about this. And there’s also the option for the use of legalized psychedelics for PTSD, which I find to be a pioneering field in the realm of mental health and autism and all this stuff.

So, there’s just lots of things I do on a day-to-day basis to make sure that I function as the person that I want to be.

Amanda Antell: Thank you. In terms of my daily life, I don’t really do a lot. I’m nocturnal, so I do a lot of my work beyond midnight and then I get up usually around 11. That’s something that’s very interesting about autistic and other neurodivergent conditions.

A lot of them are actually associated with insomnia and sleep deprivation because our brains just are more active at night. At least a lot of us neurodivergent people, and I’m definitely a classic example of that. But in terms of what I do on a daily basis, I take care of my cats. I do homework. I try to figure out what I do on a daily basis in terms of my schedule, as my executive functioning is taken up by it.

Going down to Corvallis for a class twice a week, and I spend time with my wife, of course, and we talk about our day. On days where I have less things to do or less meetings to do, I go grocery shopping and take care of all the day chores and cleaning stuff. In terms of sensory issues I deal with, I try to avoid loud sounds like smoke detectors and fire alarms.

Those sounds are like debilitating to me. In elementary school, when we had those stupid drills, I would just be in the fetal position covering my ears, because I would just be so freaked out throughout the day because I had no idea when those stupid drills would go off. In my childhood, I mentioned there were things I was punished for.

One of the things I was punished for was social situations where I didn’t interact with enough people. I can live with other people, but I do need a lot of time alone and my wife is the same way. So, I don’t have social anxiety. At least, I wouldn’t consider myself social anxiety-based. I do have general anxiety, but that’s mainly for, that’s mainly for other things.

Social situations tend to underwhelm me a lot of times because if I’m not directly engaging with someone, I get very bored, and my mind just goes off into space.

Feeling Accepted as Neurodivergent

Ash DeHart: I think we all just have a different way we deal with things.

And that’s the beauty of the autism spectrum because our minds are just such wonderful things that there’s a vast way of dealing with stuff in self-determined ways from person to person. And I will say I attended a different university before coming to PCC, and that particular university, which I’m not going to name, really did want to put the cap on autistic students, including myself.

And I did not feel accepted there. I did not feel heard. I did not feel valid, and it felt more like a money grab for various departments to have token autistic students receiving services, because when I faced a mental health crisis of extraordinary proportion that was an effect that came about because of someone else’s negative behavior, and I was depressed and sad and scared, and I didn’t know what to do, I didn’t get a lot of support from these people who supposedly cared about my welfare. It was an eye opener to me about the quality of the education at the school, the quality of the employees working at the school, both in offices and in the teaching field, and it was a huge eye opener to me that I didn’t have any value really as a human being with autism to these people.

I was simply another person that they could get money from various government organizations, NGOs, etc., for having on the roster. And when I came to PCC, I have had such a different experience. I feel accepted here. I feel nurtured here by my professors. I receive so much positivity from people that I work with and other students in class.

And from the teachers, it’s been a completely different experience, and that’s wonderful and I can’t recommend PCC enough if you’re in the Portland area. For neurodivergent students, it’s a great place to be.

Amanda Antell: PCC is pretty good for neurodivergent students compared to a lot of places. The thing of it is any other standard four year university, you’re basically a tuition check.

So, you have to kind of just look out for yourself and take care of yourself. And I’ve never really been particularly trustful of the whole mental health system at universities anyways. I’m just really too cynical for that. I’m not saying that you were wrong for expecting them to care about you because you definitely were right.

You’re a student there, you’re paying money, you’re taking classes, you’re A valid member relation, so for them to just discard you or just kind of treat you as a token is unacceptable. The thing of it is when I hear stories like that, I just find myself thinking yeah, that’s not surprising.

Ash DeHart: It’s just not in academia. It’s in generalized society, too. Neurodivergent people are tokenized at every turn. We are unicornized with a lot of people, which is horrific. We are, we are… “oh, aren’t you just inspiring?”

Don’t hand me that garbage. I don’t need to hear that. I haven’t done anything to inspire anyone. I am a human being. Please allow me to have the space to live my life with some dignity and stop trying to put me on a freaking pedestal because you think how my brain is different would be appealing to people.

People with autism deal with all kinds of stereotypes and assumptions for simply just existing. Being treated as a figurative “unicorn” is one example. Source: unsplash.com

It really disgusts me when people come with that “Oh, aren’t you just so inspirational?” Oh, my goodness. It’s insulting.

Amanda Antell: I’ve gotten the inspirational one before too, but the one I always get, which I always find so weird, it’s, oh, you must be super smart since you’re autistic and able to communicate. And I’m like, I would say I’m gifted in certain fields, but I wouldn’t consider myself particularly intelligent just because of the way that my brain is wired.

And I try to tell people, it’s kind of a toxic stereotype you’re placing on me. They’re obviously thinking of shows like The Good Doctor, like, oh my God, I hate that show. But that’s a separate topic.

Ash DeHart: The one I get all the time from people is, “oh, you’re so smart”, and “I couldn’t tell you were autistic.”

Amanda Antell: Oh yeah, I’ve gotten that one a lot too.

I openly disclose to my professors every term that I’m autistic, and whenever I do video calls with them, the first thing most of the time is, you don’t seem autistic. Are you sure you need these accommodations? I’m like, I wasn’t aware we changed forms.

Ash DeHart: I mean, do you call them out on that stuff right then and there, or do you let it slide?

Amanda Antell: It depends on the situation. For the most part, back when I first had my diagnosis, and I was still kind of getting into the groove of talking to people about it, I kind of let it slide, but now I call professors out on it, not in a way that attacks them.

Because here’s the weird thing about neurotypicals who say that to us. They genuinely think it’s a compliment. I don’t know. They genuinely think it’s a compliment. They genuinely think that they’re helping us and lifting us up by saying that we’re inspirations and that we’re super smart or that we must be geniuses or something like that.

Because obviously, “genius”, “inspiration”, they’re typically positive words, right? So, I try to tell them, “well, thank you. But here’s why that’s damaging.” It’s kind of how I approach conversations like that.

Ash DeHart: Yeah, I always try to be nice about it, and I always try to offer constructive rhetoric around this situation.

Here’s something that happened yesterday. I developed tinnitus out of nowhere, and I’ve had it for the last two months in the left ear, and it has gotten worse and worse and worse and there could be a couple of things going on here, and I see the ENT specialist in three days, but my primary care physician prescribed a lot of different medications to help with the symptoms and the side effects of this, the nausea, the vertigo, the migraines, and I spent a lot of time at the Fred Meyer Pharmacy recently picking up prescriptions because they don’t always fill them all at once.

And so yesterday I got there at one o’clock, forgetting that they closed for lunch. I was first in line, and the fluorescent lights and all the noise and the music, it just slays me, but I didn’t want to lose my place in line. And when I feel overwhelmed, I will rock, you know, or swing my arms back and forth.

And I was rocking in the line. And the woman behind me asked me what was wrong with me and was I having a mental health crisis or did I take too many stimulants. So, there was an assumption that I was mentally ill and an active drug addict. And instead of ripping her head off, I was just nice about it, and I was like, no, no, no, no, I have high functioning autism, and there’s so much stimuli going on right now that when I feel overstimulated, I need to alleviate the symptoms, so I’ll stim, and I explained it all to her and she apologized, and she was receptive, and in talking to her, it took my mind off all the excess stimulation, and I started feeling better.

Amanda Antell: Like another stigma, I get a lot on the negative side is because I’m so high functioning. A lot of people assume I really don’t need accommodation. I do have medical documentation for autism and anxiety. In fact, I’m on medication for anxiety. I have a lot of anxiety around driving just because I might get stuck in traffic, and I don’t know when I’ll be able to escape if that makes sense.

It’s like being stuck in a subway or an elevator or something. It’s just being trapped somewhere. That freaks me out.

Institutional Awareness and Training

Ash DeHart: I really think that there needs to be statewide autism training for people who work in academics, in public professions, in mental health, in all sorts of places, because I feel that it’s lacking.

If you educate people about the spectrum and how it works and how it can present itself, then people will be better equipped. with how to be most helpful and most accommodating to people like us. So, if we could get mandatory autism training going across the country and the world, that would be wonderful.

Amanda Antell: There is a caveat to that, though, because there is autistic training, quote-unquote, that’s optional in a lot of companies and even universities. The problem is it’s presented by a non-autistic person. Not too long ago, there was this email sent out about this webinar that was being hosted by this one woman about autism, and I actually emailed this woman asking about the presentation, like what her background in autism was, if she was autistic, etc, etc.

She actually did respond back and explain that she, and this is another thing I get a lot, I wouldn’t say this is a stigma, but this is something I get a lot from neurotypical people. She had an autistic relative, and therefore she thought she was an expert on autism. In living with autism, I get that a lot, and it does not make the person an expert.

It means that you can give a good book report on autism, but that is very different from actually living as an autistic person.

Ash DeHart: Exactly, because you can have all the book knowledge, and all the degrees, and the PhDs, and the MAs, and the this, that, and the other, but if you haven’t lived with it, you’re missing a component, and frankly, that’s just as horrible to me as having, let’s say, a white person play an indigenous or Asian character that you see sometimes in Hollywood.

If non-neurodivergent people feel that they absolutely must give their presentation, a solution to the situation that would be accommodating and fair is to let the non-neurodivergent expert have their say and then bring a neurodivergent person in to give their take so everyone can work in tandem.

And I don’t know why we don’t see that more, those of us that are capable of and wanting to do public speaking, maybe we could volunteer, uh, to speak about our experiences. Alongside, you know, medical professionals or academic professionals to give a more well-rounded presentation of the autism experience and the autism spectrum.

Amanda Antell: I actually do have an answer for why they don’t normally do that. So, according to my disability advisor, they consider it tokenist to ask us. I’m not f ing with you. They actually considered it tokenist to ask us, or they were afraid of coming across as tokenist. And I’m like, no, what’s tokenist is if you give the presentation, have me stand there like a cardboard cutout and not have me speak on anything.

Believe me, that’s actually my main suggestion to people give the presentation with a neurodivergent person, ideally autistic, if you’re having a presentation on autism, obviously, but. I would say at least if you’re neurodivergent, you at least have an idea of what atypical neural networking systems is like in the brain.

Question 3

What would you say that there are other stigmas you face from society, whether it’s doctor visits, family culture, or just other areas of your life?

Ash DeHart: There’s familial stigmas that I think we all have to deal with, and each one’s Familial stigma is different, but I have some of that going on in my family. I don’t get to be my authentic self with my birth family because of their belief systems.

The Iron Front logo is commonly used to represent anti-fascism. Source: Wikimedia Commons/public domain.

They are a certain kind of religion where who I am. With a gender identity and sexuality as a pansexual is not accepted where my choice of political philosophy of anarchism and antifascism is not accepted, and where they’ve never made an effort to understand me as an autistic person. I don’t think they’ve even ever asked.

You know, I love them because they’re my birth family, but I don’t really get to be who I want to be with them. And so that’s why my contact is pretty limited to just a few people in the family who are a little bit more accepting. At the doctor’s office, I find now that there’s not as much stigma. It used to be horrific when I was younger.

Another area I’d like to talk about stigmas in autism and neurodivergence is sexuality. I have found that people make judgments about the sexuality of autistic people. I have gotten so many comments from people that will question you.

Oh, do you like sex? Are you more sensitive than other people? Do you come quicker than other people because of your autism? Are you asexual? What’s your deal? What’s the deal with autistics? And I find it highly offensive because it’s none of your business what happens in my bedroom with who I choose. And I don’t appreciate it when people, out of ignorance, start speaking to me in that fashion. It’s different if it’s a close friend or a prospective partner. I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about relative strangers just throwing the door open and asking all kinds of questions that they have no business asking. When people do that, I very politely tell them that’s really none of your business and have a nice day.

I think other stigmas in general, uh, stigmas around stimming, stigmas around rocking, stigmas around hand clapping, stigmas in the classroom when you’re super, super, super smart.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, I’m sorry I had to go through all that. Um, honestly, from the sexual ones, I almost feel like they were sexually harassing you, quite frankly, and you’re a lot nicer than I would have been. I would have just told them to f off. Nah, I don’t put that s t. Like, when I’m out in public or on public transport, I’m pretty aggressive.

I just tell people to f ing get the f away from me. Especially if I’m tired and sleep-deprived. I just have no time for that s**t. I’ve never really got a question on my sexuality, to be honest. I’m not sure if it’s because I’m white, and maybe there was some kind of fetishizing happening with you, ’cause I don’t know.

I’ve never met you in person, but it’s like, I have heard that minority groups tend to get like fetishized by white people a lot, so I’m not sure if that’s what was going on with you as well. And I apologize if that’s offensive. I don’t know. Maybe I’m wrong?

Ash DeHart: I am white presenting, even though I have indigenous blood.

I am physically very attractive. I can’t help that. It’s just how the ball bounced.

Amanda Antell: I’m not saying that’s your fault at all. No. That’s never your fault.

Ash DeHart: No, but I do make an effort to try to educate people and be nice about it. But at some point, if it continues, I’m just like, f k off, please. I have learned to be a little bit more stand your ground in those areas as of late.

You know, not everyone deserves my niceness.

Amanda Antell: I would say if anyone’s bothering you like that, I don’t think they deserve your niceness at all. They’re being rude to you. They’re coming up on your space, they don’t have permission to be there. Tell them to f k off. They’re not entitled to your time, is what I would say to that.

Ash DeHart: And I’m starting to learn that as my self-esteem increased with therapy as I got older and gained some wisdom and knowledge about life and myself and who I was, as I became more comfortable in my own personhood and didn’t have to apologize for existing so much, I’m able to catch myself now when I participate in that old behavior of Oh, I’m just going to be nice because I don’t want to rock the boat.

Coming up as a youth and in the earlier portions of my adult life, there was a stigma of always having to be well-behaved and always having to be nice, and never showing how I truly felt because I didn’t want to be abused or verbally attacked or ad infinitum the things that could happen around simply being myself.

And while I do always try to take the experience, whatever it is, and turn it into a learning experience for myself and the other person, sometimes that just can’t be done, and I no longer have to pivot to that old behavior of “well, let me just be a good Ash and not rock the boat because I spent a lot of my life in the earlier years not rocking the boat, being a people pleaser and a doormat for all kinds of negative behavior that I indeed signed myself up for because of my consent by not standing up for myself.

And now I know better. And now, generally. I don’t have to deal with that so much, but when I do slip into “let me always be nice” when it’s not warranted, I have to correct myself. Autistic people, not all of us, but some of us can get ourselves in a lot of hot water because we’re always trying to be nice.

We’re always trying to be helpful. We’re always trying to not rock the boat. And that can come in the form of narcissistic abuse, domestic abuse, sexual abuse, All kinds of stuff. We are super vulnerable to a lot of that because of our varied spectrums. There’s a lot of positive things about the spectrums, but then there are things too that can open the door.

To things that are negative and it’s not our fault. It’s just the way that it is. The fault lies with the people out in the world who take advantage of people like us.

Masking

Amanda Antell: I was just going to say that a lot of what you’re talking about, being a people pleaser, being a doormat, etc, etc. A lot of that has to do with being raised as women.

I don’t know, I apologize if I’m making any presumptions about what your former identity was, but I just recognized that a lot because that’s just how I was raised. And believe me, I got into trouble a lot. One thing that makes me very different from other autistic people is that I never really have masked.

Maybe I masked a little bit, but I don’t ever remember doing that as a kid. And I would get in so much trouble. I just did not have it in me to do it. I don’t, I just never cared what people really thought of me. And even if I got punished for it, it just didn’t change the outcome. It’s like, okay, I might get spanked, I might get yelled at, it’ll pass.

I was still scared, but I knew it was gonna, I was gonna, it was gonna pass, and I knew I was gonna be alive at the end of it. The one thing that also made me kind of weird as a kid is the fact that I never actively sought out acceptance by groups, whether it was family or social, I just was, I don’t know, I guess I always had the assumption that I wasn’t gonna be accepted anyway, so why bother?

Masking is a term to describe how people with autism hide parts of themselves to fit into neurotypical society. This can be extremely harmful, especially over time. Source: Image made using Adobe Firefly.

I’m not saying that I was like this anarchist kid or anything like that, but I definitely did handle social situations very differently and definitely different from how my mom wanted me to handle situations just because I did not care if people liked me or not.

Ash DeHart: I’m sorry that you had to go through all that, but it’s wonderful that you didn’t mask.

I’m sorry that you were abused because you didn’t mask. I unfortunately had to mask because it was demanded by the people that raised me. And yes, I grew up as a cis female. I am a cis female. I do not present androgyny to people being nonbinary. Sometimes I dress like a boy. Sometimes I look more feminine.

Sometimes it’s somewhere in the middle. For me, the masking presented itself in a very specific way. And I want to put a trigger warning here for any listeners. There’s going to be some discussion about sexualization. Of children and things of that nature. I was sexualized young. As a child, because I was really pretty and so that was coming not only from the home, but also from boys at school from a very young age, young, young, young, young, young.

And so, 1 of my masking techniques. was to be the prettiest, the smartest, the most polite, ad infinitum. And as I grew older and started playing in bands, I started doing burlesque. I had a positive experience in the sex industry. It wasn’t the industry that hurt me. It was the people around me that I knew that took advantage of me and hurt me the most in the music industry and in my day-to-day life.

Podcast guest Ashes of the band Dead Letter Era. Source: Image provided by artist.

Because the big masking technique for me was to present this beautiful person who could sing and play instruments and dance and he was fun and smart and could party. And it worked for a long time until I became addicted to alcohol and heroin, until I realized that wasn’t the person I wanted to present anymore, and I wanted to be my legitimate self.

And so, coming into Clean Time 10 years ago, almost, began the journey of learning how to take the mask off and be myself. And it was a long, long journey. And the journey is never ending because I learn things about myself every day. But through clean time, and sobriety, and counseling, and all kinds of things, I finally learned how to just be me without the mask.

And that is like the most relief that I think I’ve ever had in my existence on this planet, when I realized I didn’t have to mask anymore. It came later in life for me. Some people get it young. Some people don’t, but I’m glad that I have taught myself and used the tools that were offered to me to become an authentic Ash, an authentic human being, that I don’t have to hide behind societal demands, societal expectations, societal stigmas anymore.

I can just be me. And it’s a wonderful place. I don’t regret my past experiences. Again, you know, I just appreciate the opportunity to come here and, like, speak publicly about this kind of stuff. This is really the first time that I have spoken publicly about my autism, my substance abuse, my abuse as a child, etc.,

etc. I’ve spoken publicly on other things. I’ve spoken about gender and this, that, and the other. But never all of this together and I want to thank you for providing a platform and a safe space for people like us Just to you know air out the laundry and talk about what our life is like

Amanda Antell: Thank you for being here and just being brave enough to share your story and just so you know This is a safe space.

I’m never trying to catch you off guard and if you ever want something edited out after the fact just, I won’t even ask why i’ll just do it I want people to feel safe on this podcast and I want them to know that they’re accepted as they are here and you are certainly no different.

Ash DeHart: Right on, I didn’t plan what I was going to say, because you know how Autistics, we sometimes like to plan what we’re going to say ahead of time.

So, I didn’t do that. I didn’t even look at the questions really beforehand. I kind of glanced at them. But I decided for this I wanted it to be almost like guerrilla style. I wanted it to be off the cuff and brutally freaking honest. There’s a method in filmmaking called guerrilla filmmaking where you shoot the scene as if you’re LARPing like live action role play.

Let’s say an example would be you’re shooting a subway scene. So, everyone will just jump on the subway. and start running their lines in front of unsuspecting people while the director and the cinematographer films it. I’m a big, huge fan of improv. of improv speaking, I do improv music, improv acting, improv art.

I think it taps into something at a deep subconscious level that we may not always get to tap if we are rehearsing our answers or our actions beforehand. Not that that’s a bad thing, but for me, there’s other ways to do things. And I try to embrace different ways of doing things in my life to have a super full life experience.

Amanda Antell: No, that’s a really beautiful way to live. And by the way, I don’t know. In case you don’t know this, or if you don’t hear this enough, what happened to you as a child, especially the whole sexualization thing, that was never your fault, and that’s totally on men or women who sexualized you. It was all their fault, not yours.

Ash DeHart: I really appreciate that. And I, I’d like to say something to you and to the listeners. Yeah, go ahead. This is deeply personal, but I want to share it, because I don’t want anyone to ever have to feel the way that I did. But I came here alone, not knowing anyone, the landscape of the city had changed so much, so many people I used to play music with back in the day have died or moved on, many activists that used to be here, no longer here, I spend a lot of time alone.

I became very, very depressed in the midst of therapy, in the midst of making all this progress. I got hit with a wave of depression that I could barely chew, let alone swallow. And I wasn’t really receiving the kind of support that I needed from folks at the university. It was just a lot of lip service.

I was tired of trying so hard and yet sometimes Ending it with the short end of the stick. Doesn’t matter what I did. And so, it all just hit at once. And the funny thing is, I had an appointment that day at Vocational Rehab to do an intake because if you know about Vocational Rehabilitation, they help people like us get jobs and all kinds of things that we need to make our life better.

And I went in and I sat down and My case manager at VR, he could tell something was wrong, and he sat and asked me how he could help, and he sat there and listened to me for a good half hour just cry out everything that needed to come out that my autistic self had just been holding onto because there was really nobody to share it with because I didn’t have any social support.

And that simple act of listening Opened up a door for me that let me know someone cared because at that point, I wasn’t talking to anyone in my family because my partner had done some things to try to pit my own family against me out of hate when I left and would not return. You know, so if you’re out there and you feel alone, if you feel like your life has no worth, if you feel like you’re addicted and you can’t stop drinking or using, if you feel overwhelmed by the capitalistic system and the political systems and the systems that are in place that oppress all of us and you feel isolated, And you no longer feel like you have a place on this planet, there is help out there.

Please, reach out for help, because we need people like us. The world needs neurodivergent people to change the s t that we currently live in. Because we have a way of looking at things, we have a way of seeing things, we have a way of putting in things into motion that are positive and helpful. And I truly believe we have the potential to help change the planet.

for the better. So please reach out for help like I did because two years later, I have this amazing life. I have social support. I have a great job. I’m doing well in school. I’m still struggling making friends, but things are getting better on that front, and I just want to encourage any listeners out there if you’re feeling overwhelmed and that you can’t do this anymore, there is help out there.

There are people that care. There are people that understand us as neurodivergents. Reach out, get the help, you know, heal, become the person that you want to be, and then take who you are, and make this planet a bigger, better place, because we don’t have to live under these yokes of oppression anymore.

Amanda Antell: I kind of wish we were in person right now, because then I feel like I, I don’t know, I would, I’d want to give you a hug, but I also don’t know if that would be okay, because I don’t know how you feel about other people hugging you. But either way, I want you to know that you’re doing great and thank you so much for sharing your story.

That was very brave of you, and if you ever need me outside of this podcast, just feel free to shoot me an email.

Ash DeHart: Likewise

Amanda Antell: Again, you’re doing great, Ash.

Ash DeHart: It means so much to me that I can be present that I can be present and show up for life, that I can make a difference in the lives of people in my community, in the lives of people at my school, in the lives of people in Portland, and maybe one day even beyond.

It feels so good to know that my life has meaning.

Amanda Antell: I want you to know that your life has meaning, the way you get, I don’t know, one thing I want people to know is that you determine the meaning of your life on your own terms. Don’t ever let other people determine what your life means. It has to come from you.

Ash DeHart: Thank you for that. It took me a long time to learn that, but when I did, it was like the light bulb went off and I could thrive. So, thank you for reiterating that to me and to the listeners. It’s been a real pleasure to be here today and thank you so much for having me.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, and you’re an amazing person, Ash. I really hope you know that, and I really have so much respect and admiration for you as a person, your story, your experiences, what you can give other survivors and people like coming out of really abusive and bad situations.

I know you want to run for city council and become a lawyer. I know that we’ve talked about like people might use your past against you, but to me, I would just run with your past and just say this is what would make me a good candidate because I know what it’s like to struggle. I know that people are struggling, and this is why I’m going to do my damnedest to help people out as fast as I can.

Ash DeHart: Thank you for that. I think many people, especially neurodivergent people, hide their past or don’t step out into areas where they could be a benefit to others for fear of things in the past. And so, we just have all kinds of neurodivergent people and non-neurodivergent people to just hiding in the wings who have such wonderful things to offer society who could create lasting change but who live in the fear of what people might say or do or think.

And cancel culture and this, that, and the other–it is okay to step up and say, yes, I did all these things. I made mistakes. I did the best I could at the time with what I had, but I am no longer that person, and so there has to be some degree of acceptance in society, because I’ll fall short of the mark here and there.

And no one should be judging anyone really, and I, I encourage listeners today, you may have had a spotty past, you may have done things that you’re not proud of, but we’re all human and we all make mistakes.

Please don’t let a spotty past stop you from a wonderful now and a great future.

Closing Comments

Amanda Antell: Yeah, I agree with that 100%.

Are there any other things you want the public to know about the stigmas about autism and other disabilities?

Ash DeHart: We’ve covered so much ground in this hour. I think a lot of what I wanted to say has already been said. I will say to the neurodivergents listening, never be afraid to be yourself, because it does not matter what anyone else thinks.

And to the allies, and to the parents and family of neurodivergents here, and the friends, I’d just like to say thank you for your support. Thank you for your support for our community. It can be frustrating dealing with people like us sometimes, but please remember, always to act in love. Always act in love.

And everything will be okay.

Amanda Antell: And for me, I want to remind allies and other advocates that there’s a very fine line between helping us speak up and speaking over us. Once you start speaking over us, then you’ve crossed a major line. And then you become part of the oppression problem.

Ash DeHart: Exactly. And you frame it in a really good frame because it is oppression, and oppression is something we don’t need in our spaces. And with that, I just bid everyone a really great rest of your afternoon and a fabulous weekend.

Amanda Antell: Thank you so much for joining me today, Ash. I had a great conversation and I hope you join me for another podcast episode.

Ash DeHart: I definitely will. Best to all the listeners out there. Thanks so much.

Conclusion

Loving our neurodiversity is important for building a more accessible world. Source: Image made with Adobe Firefly .

Amanda Antell: Thank you for listening to today’s episode of Let’s Talk Autism. I hope you truly gained an appreciation for how disability stigmas can affect autistic and other neurodivergent people and why they should be avoided. In general, it is best to have an open and honest conversation with neurodivergent people about their conditions, so they feel safe enough to unmask and be their authentic selves.

As Ash mentioned in this episode, evolving from a victim to a survivor is dark and can take us to the most difficult periods in our lives. To leave a bad situation means we give up the twisted stability of it, leaving us vulnerable to a barrage of new risk and uncomfortable experiences. I’m truly grateful and in awe of Ash for sharing their story and the strength that it took to get to this point.

If you are considering suicide or going through any kind of abuse, please talk to someone you trust or reach out to the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. Thank you for listening and I hope you join me for the next episode.

Thank You for Listening

Chrispy Jones: Thank you for listening to Let’s Talk, Portland Community College’s broadcast about disability culture. Find more information and resources concerning this episode and others at pcc.edu/dca. This episode was produced by the Let’s Talk! Podcast Collective as a collaborative effort between students, the Accessible Education and Disability Resources Department, and the PCC Multimedia Department. We air new episodes bi-weekly on our home website, our Spotify channel, and on XRAY 91.1 FM and 107.1 FM.

Listen to Ash’s music project Dead Letter Era here on Bandcamp.