Resources, Reports & Research

Resources

Bees

Bees. When you think of them, you likely think of honey bees. Maybe bumble bees.

Honey bees are not native to North America. Originating around the Mediterranean and imported to the US from Europe hundreds of years ago, honey bees were not brought to Oregon until the 1860s. A stalwart workhorse in the pollinator world, honey bees provide us with the sweet, sticky, delicious benefit to all their hard work: honey. Honey bee populations have declined in the last few decades, threatened by disease and parasites.

Bees are critical to our environment and to our survival. More than three quarters of the world’s crops are at least partially dependent on pollinators, including our fuzzy friends. While we strive to protect and bolster threatened honey bee populations, including those in our campus apiary, we also encourage and support native bees.

Over 4,000 types of bees are native to North America. In our Oregon region, there are over 500 species of native bees.

Unlike honey bees, our native bees are primarily solitary, not swarming, and are not aggressive. As well, they have a much smaller range, some living their lives within 300 feet of their nests.

Native bees

Here is some basic information about bees native to our area, including information about building your own mason bee house.

Bumblebees

There are 16 species of native bumblebees in the Pacific Northwest. The only native bees that are social, they live in small colonies, usually of less than 100, and while non aggressive, bumblebees can sting when threatened. Serving a critical pollination role, these incredible little creatures can haul a big load, carrying up to 90% of their body weight in nectar and 20% in pollen. Each species of bumblebee has a slightly different appearance and coloring and specializes in pollinating a specific range of flower varieties.

Bumblebees have the ability to buzz pollinate, meaning they vibrate their indirect flight muscles causing the pollen to explode off the flowers’ anthers onto the bee. This makes bumblebees particularly critical to those plants requiring buzz pollination, including tomatoes.

Carpenter bees

Though these bees are not social, they may burrow near each other, frequently nesting in exposed dry wood. Carpenter bees are efficient pollinators of open faced flowers, preferring tree and cane fruits. Some species of carpenter bees are loud flyers, their wings making a very noticeable buzzing sound.

Nearly hairless, these are more primitive pollinators, swallowing pollen to transport it then regurgitating it in the nest. Approximately five species of carpenter bees are native to the Oregon region.

Leafcutter bees

Leafcutter bees are so named for their nesting behavior. Using their large mandibles, the females cut bits of leaves to line their nests sited in rotten wood, cracks or holes in wood, and pithy plant stems. Not aggressive, these solitary bees are effective pollinators for field crops including alfalfa and clover.

Over 40 species of leafcutter bees are native to Oregon.

Long-horned bees

Approximately 25 species of these fuzzy bees are Oregon natives. They have robust bodies, vary in color and the males have unusually long antennae. Nesting in tunnels in the ground, these pollinators prefer sunflowers, daisies and flowers & herbs grown for seed.

Mason bees

Approximately 70 species of mason bees are Oregon natives. Ranging in color from metallic blue to green, sometimes black, these smaller bees are frequently mistaken for flies. Solitary, these bees nest in small tunnels or tubes, including in the pithy stems of cane fruit such as raspberries. Mason bees are an easy neighbor, non-aggressive and very local preferring to forage within a few hundred feet of their nests.

Mason bee larvae, houses and tubes are widely available for backyard installation. A fun and educational activity, caution should be exhibited to not further endanger native species. Only obtain your mason bees or larvae locally and only purchase species that are native to your area.

Miner bees

These small solitary creatures excavate nests in the ground, thus the name miner or mining bee. There are hundreds of varieties of miner bees in Oregon, none of which are aggressive. Female miner bees build an underground tunnel network, laying a single egg on top of a ball made of pollen and nectar (food for the emerging larvae) in each tunnel branch. A bit smaller than honey bees, this bee feeds on a wide variety of plants and is a main pollinator of blueberries and early spring blooming fruit trees.

Sweat bees

Sweat bees are common in many Oregon crop growing regions. More than 26 species of these solitary bees are native to Oregon and nest in tunnels in the ground. Sometimes they share tunnel entrances. Collecting pollen on the underside of their abdomens and hind legs, they pollinate many varieties of plants and prefer clover, marigold and zinnia.

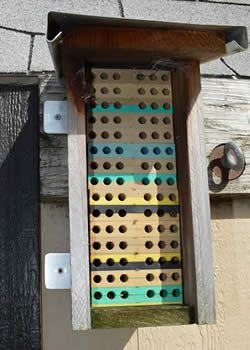

Mason bee houses

It’s easy to get started with mason bees.

There are three primary types of mason bee houses

- Stacked wood mason bee house at RC

- Tubes

- Wood block mason bee house at RC

Build your own mason bee house

There are many resources to help you build your own mason bee house. It’s easy and rewarding! A few key tips before you begin

- Use only untreated wood

- Protect your bees from predators – install chicken wire or landscaping mesh over the openings to keep predators out

- It is helpful to build some sort of overhanging ‘roof’ or other means to protect the nesting tubes from water getting in and creating mold

- The nesting holes need to be 6-8” deep to allow the bee to lay both male eggs (only placed at a shallow depth) and female eggs (placed deep in the nesting hole)

- Do not reuse uncleaned nesting holes – because of this, the wood block style may not be the most advisable unless you build it to accommodate paper tubes inserted into each hole

- Houses (and cocoons-see below) need to be cared for and cleaned each season

- Leave room above the nesting holes to place the soon-to-emerge cocoons each spring

There are many sources for specific build directions. We recommend you do a little research before getting started.

Purchase your mason bee house

Mason bees and houses are widely available for purchase. Take care to purchase only locally sourced bees and cocoons so as to not introduce any threat to the native species.

Siting your mason bee house

Mason bees like early morning sun in the spring, shade during the heat of the summer and protection from the wind and rain. Install your house on a South, or possibly East, facing wall under the eaves. Protect the bees from predators and cover the openings with chicken wire or landscape mesh to allow the bees in and keep the predators (including blue jays and mice!) out.

Mason bees need clay mud to nest, so make sure you site your house near a source of mud, or place a container of clay mud nearby – and remember to replenish the water as needed to maintain a mud-conducive moisture level.

Care and attention

If you are purchasing cocoons, they likely come in little paper tubes. Insert these into the hole in your mason bee house after installing it in the optimal location. Then watch for your bees to emerge in early spring and do their thing!

Overwintering

Special care needs to be taken to ensure the viability of your bees for spring. Protection from predators and weather will help the cocoons survive. There are many tutorials and YouTube videos that can help you with this.

The key overwinter care steps include

- Removing the cocoons from the house: Open the house (if possible) and remove the tubes. Carefully remove the cocoons from the tubes into a shoe box, plastic tub or other container.

- Checking for parasites: Carefully inspect each cocoon and remove any parasitic larvae.

- Clean the cocoons: Wash the cocoons in a dilute bleach water and dry.

- Store the cocoons: Place the cocoons in a lidded mouse-proof container, plastic, glass or metal, with small air holes (no greater than 5/16” – pencil width). Store the container in a cool dark place until approximately mid-February.

While keeping mason bees is not difficult, it does require some planning and care. We recommend you do a little homework before beginning.

General care, tips & trouble shooting

Oregon State University Extension Service has a wealth of information.

Other interesting bee stuff

The oldest bee fossil ever found: Oldest ever bee found in amber

Bees vs wasps

How do you know if what you see is a bee or a wasp?

| Bees | Wasps* |

|---|---|

| Bees are pollen collectors – they have fine hair that captures pollen | Wasps do not collect pollen |

| Because of their hair, the bees look fuzzy | While some species have hair, they do not appear fuzzy |

| Rounded bodies | Elongated bodies |

| Less aggressive than wasps | More aggressive than bees |

| Can sting once if at all | Can sting multiple times |

| Feed on pollen | Feed on fruit, nectar, sugar or protein |

* Note – yellow jackets are wasps

Plants for Pollinators

What are pollinators and why do we care?

Pollinators are creatures that pollinate flowering plants and trees. These creatures include ants, bats, bees, beetles, birds, butterflies, flies, moths, wasps as well as other animals.

These pollinators are responsible for assisting over 80% of the world’s flowering plants, and nearly 75% of our crops. This is over 180,000 plant species and more than 1200 crops. That means that 1/3 of the food you eat is dependent on pollinators. The impact on the global economy is $217 billion with honey bees contributing between $2-6 billion annually to the US agriculture productivity.

Pollinators frequently go unnoticed as they go about their business carrying pollen from one plant to another, but without them, our lives would be vastly impacted. From fruits and vegetables, to nuts and berries, to chocolate and coffee…all are dependent on pollinators. In addition to the food that we eat, pollinators support healthy ecosystems that clean the air, stabilize soils, protect from severe weather, and support other wildlife.

The vast majority of the seed plants in the world require pollination. This is true for flowering plants and cone bearing plants including pine and fir trees, both critical to our Northwest region.

What’s the problem?

Many populations of pollinators are in decline and some species are at risk. Major contributors to this decline include:

- Loss of feeding and nesting habitats

- Pollution, use of chemicals

- Herbicides and pesticides

- Disease and parasites

- Climate changes

- Monoculture

What can I do?

The single most impactful thing you can do is create a pollinator habitat. This can be large or small, structured or riotous, and can be established anywhere. Small containers of shrubs, parking strip plantings or sprawling fields of wildflowers are just a few options. Planting pollinator-friendly plants with overlapping bloom times will not only create a Spring through Fall garden for you, but a year-round pollinator habitat.

Supporting pollinators also provides additional benefits including:

- Creating cover and food for other wildlife

- Improving the habitat for other beneficial insects

- Reducing the reliance on pesticides

- Improve water and air quality

- Stabilize the landscape

- Bolster our declining honey bee population

How do I know what plants will help?

We can help! Check out this handy list.

What if I need more information?

There are many resources for information, instructions and assistance. Here are just a few specific to our Portland Metro area in the Pacific Northwest:

Tips & Resources for Food Growers

Every gardener has to start somewhere. Here are some basics!

- You’ve got to start with healthy plants. Whether you are purchasing from a nursery or planting what you seeded yourself, remember to look at the whole plant, not just the top. Check out the root system and make sure it is not root bound. If a plant is root bound, this means the plant has been in its pot for too long and that it may not be getting the nutrition it needs from the soil because there simply isn’t enough potting soil left.

- Watering is the second most basic step to caring for plants. When it gets consistently dry, we’ve got to help out some of our more sensitive plants – especially those that are newly planted. Keep up on watering and make sure the soil is damp.

- A good layer of mulch goes a long way in the plant world. A 2- to 3-inch layer of mulch conserves moisture and blocks sunlight from the beds. Without light, weed seeds can’t germinate and become a problem. However, keep mulch several inches away from the bottom circle around established plants.

- Adding organic matter to your soil will improve it. Depending on what type of soil you have, sandy or clay-like, composting will enhance its water-holding capability or increase the soil’s drainage, respectively.

- Steer clear of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers like Miracle-Gro. Everyone wants the food we serve to ourselves and families to be safe and healthy. This desire for safety is the central reason people grow organically. The more we learn about chemical herbicides and pesticides, the more we see the effects of synthetic fertilizers and genetically modified crops, the more we realize that we must protect ourselves from them. Don’t panic, grow organic!

Helpful online resources for food growers

- OSU Extension Service Garden Calendar (free monthly suggestions for garden care)

- Planet Natural (gardening research center and supply)

Local seed and supply companies

- Adaptive Seed (Sweet Home)

- Territorial Seed (Cottage Grove)

- Naomi’s (Portland)

- Concentrates (feeds, fertilizers, salts in Milwaukie, OR)

- OBC Northwest (garden and commercial supply in Canby)

- Ed Hume Seeds (cool climate varieties, PNW)

- Wild Garden Seed (Philomath)

Other supply resources

Dripworks (irrigation)

Local and regional flower-focused resources

- Swan Island Dahlias (Canby)

- Frey’s Dahlias (Turner)

- Dan’s Dahlias (Oakville, WA)

- Gloeckner & Co. (Irises! Clackamas)

- Brooks Gardens Peonies (Brooks)

- Adelman Peony Gardens (Salem)

- Pacific Northwest Cut Flower Growers Facebook group

- Floret Flowers (Mount Vernon, WA)

- Nationwide directory to shops that sell USA-grown flowers

Composting resources

Local Garden Maps

Reports

Learning Garden Annual Reports

- 2017 Learning Garden Annual Report

- 2016 Learning Garden Annual Report

- 2015 Learning Garden Annual Report

- 2014 Learning Garden Annual Report

Learning Garden Master Plan (2015)

This Learning Garden Master Plan (2015) is the culmination of two years of engagement with PCC students, staff, and faculty. Scott Edwards Architecture, Lango Hansen Landscape Architects and Fortis Construction helped complete the process. The Rock Creek Sustainability Office is currently seeking a funding source to cover the $675,222 bring this project to fruition

Bee Campus Annual Reports

Research

Student Work

We frequently serve to provide opportunities for students to focus their course projects on sustainability and garden related topics. Research, planning, writing and pilot testing ideas are some of the endeavors students undertake as part of their coursework. We appreciate being able to support students in this way as well as receiving the benefit of their studies. When possible and practical we assess the feasibility of implementing the recommendations from student work into our planning and practices. Faculty and students interesting in exploring options for academic collaborations should contact the sustainability coordinator.

Samples of previous work include:

2016 Wildlife Habitat Enhancement Plan for the PCC Rock Creek Learning Garden

2013 Canada Thistle and it’s Creeping Roots

2013 Composting, the Problem with Compostable Plastic and Possible Solutions

Outside Research

We are frequently contacted by researchers outside the immediate PCC community. We support information requests as our resources allow. We appreciate the benefit when the researchers invite us to share their work.

2016 Vermicomposting: the Future of Sustainable Agriculture and Organic Waste Management