Let’s Talk! Autism and the Gender Spectrum, Talk 2 with Eugene and Ericka

Hosted by Amanda Antell. Produced by the Let's Talk! Podcast Collective. Audio editing and transcription by Carrie Cantrell & Chrispy Jones. Web Copy by Nic Meza Honea. Webhosting by Eugene Holden. Visual editing by Ryan Vail and Erik Wideman.

From a young age girls are told by society what they are allowed to do with their bodies. Source: Unsplash.com.

Understanding the Medical Struggle

Article by Nic Meza Honea, Edited by Carrie Cantrell

March is Women’s History Month. Across the nation, we explore the vital roles women play in everything from politics to industry to art and everyday life. In this episode, Amanda and her guests explore mental health support and what that looks like along the gender divide for women, men, and people who fit somewhere in the middle or fit nowhere at all.

2017 Women’s March on DC. Source: VOA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The historical concept of women’s health is rooted in gynecology, and so is the inequality of women’s treatment in healthcare. Hysteria was a common diagnosis, with even the origin of the word pertaining to women. It comes from the Greek word hystera, which means uterus.

The history of mental health treatment for women is not just concerning but disturbing.

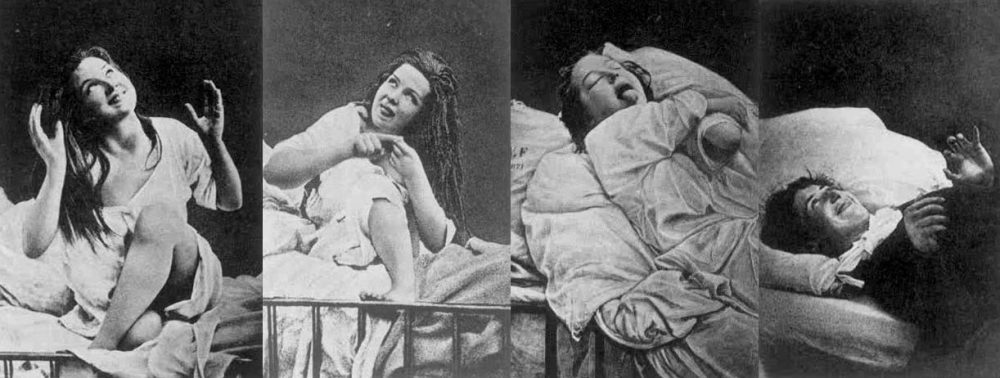

An 1880 depiction of women in hysteria. Source: Damiens.rf, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

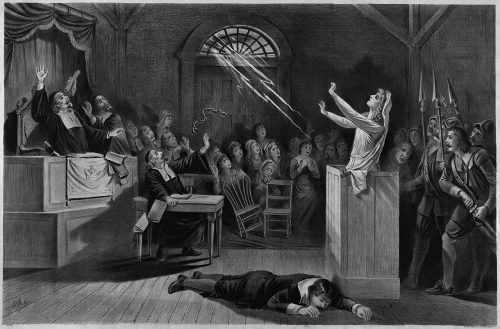

In the past, a prognosis of “hysteria” would include a range of treatments, including special herbs, prescribing sex or the abstinence of sex, fire purification or hanging as a witch, and psychoanalysis or institutionalization, among many others.

Today, although diagnosis and treatment for hysteria are considered very outdated, the condition was only removed from the DSM in 1980. Biases against women, AFAB (Assigned Female At Birth) people, and other non-conformers exist within the healthcare industry and scope.

Many cases of diagnosed hysteria were determined to be the work of witchcraft. Representation of the Salem witch trials. Lithograph from 1892 by Joseph E. Baker. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

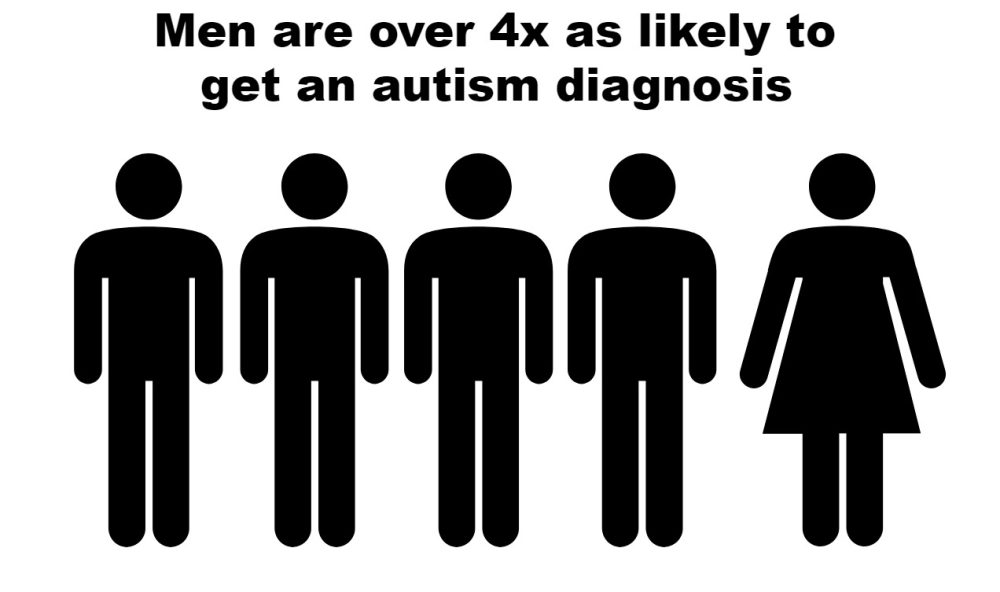

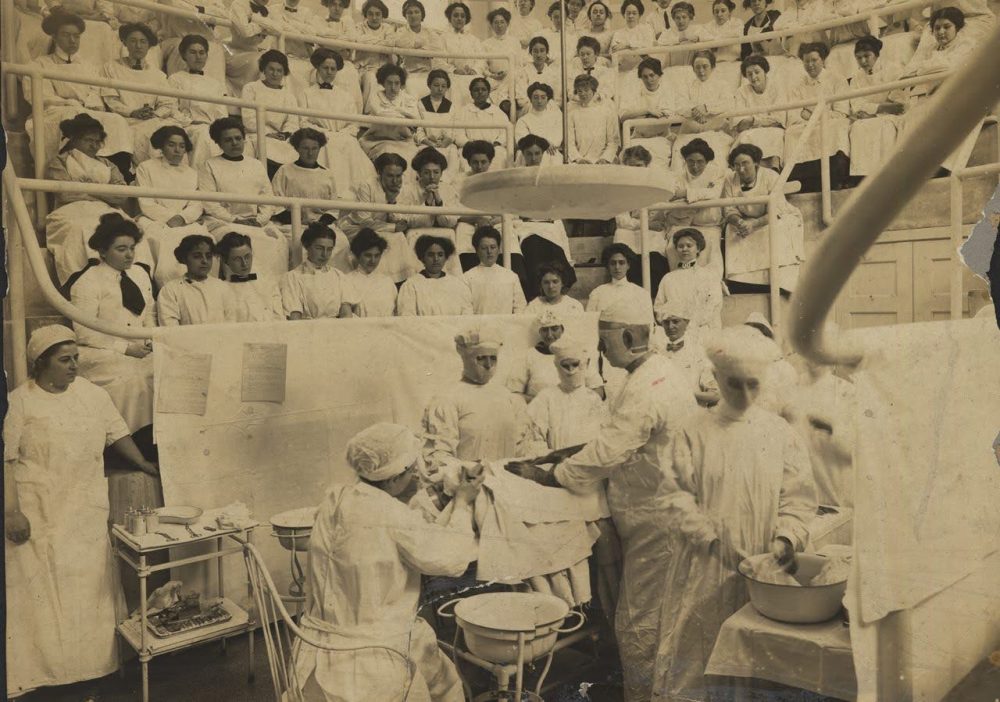

An imbalance of having more men in the medical field has proven difficult for women or non-binary individuals seeking gender-affirming and or sex-specific care. Because it was not required to include women in nationally funded health studies until 1993, current research and knowledge of women and AFAB within the medical field are still catching up. What we do know is that women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression, more likely to be prescribed certain medications, and in some instances, be misdiagnosed and receive extreme outcomes.

Today, more and more women are entering the medical workforce. This has given a boost of support to women seeking healthcare from practitioners who understand their perspective. In parting words of advice to the audience, Erika reveals the necessary courage women have when it comes to disclosing their neurodivergent condition.

“If they choose to share their diagnosis with you, respect it, take it seriously. Ask them questions if needed. And then also just understand that there are intersections between gender and sexism.” -Erika Donohue

Let’s Talk: Autism

The Gender Spectrum, Part 2

Hosted By: Amanda Antell

Guest Speakers: Eugene Holden and Erika Donohue

Produced by: Let’s Talk! Podcast Collective

Released on: 03/15/2024

Amanda, Eugene, and Erika discuss disability, spectrums of disabilities and visibility, and the difficulty many neurodivergent people have in having their disabilities recognized and taken seriously.

Let’s Talk! Autism and The Gender Spectrum

Transcript edited by Carrie Cantrell

[00:00:00] Introduction to Let’s Talk: A Space for Sharing Perspectives

Chrispy Jones: You’re listening to Let’s Talk! Let’s Talk! is a digital space for students at PCC experiencing disabilities to share their perspectives, ideas, and worldviews in an inclusive and accessible environment. The views and opinions expressed in this program are those of the speakers, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Portland Community College, PCC Foundation, or XRAY.FM. We broadcast biweekly on our home website, pcc.edu/dca, on Spotify, and on XRAY 91.1 FM and 107.1 FM.

We broadcast biweekly on our home website. PCC.edu forward slash DCA on Spotify and on X-ray 91. 1 FM and 107. 1 FM.

Carrie Cantrell: Hi everyone. This is Carrie Cantrell, one of the producers for Let’s Talk! Podcast Collective. Stay tuned at the end of our episode for a special announcement from one of our field reporters.

[00:00:54] Exploring Gender Identity Through the Lens of Neurodivergence

Amanda Antell: welcome to another episode of Let’s Talk Autism. My name is Amanda, and I’m the facilitator, host, and producer of this series. Today we continue the exploration of how ADHD and autism interact with gender identity in binary and non-binary communities. I’m joined today by Erika and Eugene, who share how their diagnosis has impacted their gender identity journeys.

In this conversation, you will get interesting insight in how autism and ADHD can influence how someone can experience their gender and their reactions to gender norms. With this in mind, this conversation presents how gender norms can influence people with ADHD and autism, as well as their choice to ignore or accept them.

Either way, this podcast episode provides an excellent breakdown of how neurodivergent people adapt to social constructs and create their own roles to survive.

[00:01:37] Personal Journeys: ADHD, Autism, and Gender Identity

Erika Donohue: My name is Erika, my pronouns are she/her, I am not in school at the moment, but I previously studied music and forestry, I have ADHD. I got an update since the last episode I participated in; I was actually diagnosed at eight years old.

Eugene Holden: My name is Eugene. My pronouns are he/they. My major right now, I’m in grad school, studying to be a special education teacher. And my undergrad is in Geology and space and planetary science, and my occupation, I currently work at, as an advocate and in the alternative formats department, and I also work as a substitute in a local district. And I am autistic, I was diagnosed, think about 2 years ago as an adult, and then I’m being evaluated for ADHD as of recently.

Amanda Antell: Awesome. So, my name is Amanda. I use she/her pronouns. I have autism and was diagnosed at age 31 and I’m currently finishing up an animal science degree at Oregon State so I can apply to vet school next year.

[00:02:49] The Impact of Assigned Gender on Diagnosis and Perception

Amanda Antell: So how did your assigned at birth gender influence your ADHD or autism, assessment process or diagnosis process?

Eugene Holden: I think my assigned gender at birth did influence my autism assessment for sure. I was assessed as an adult with self-referral because I finally put the pieces together. As a kid I was raised female, I was just like the quiet, shy, very easy to cry kid. And I think that was seen as oh, I’m just like a quiet girl, but it was more like I was having, like meltdowns and difficulty with emotional regulation and stuff like that. And it just kind of went unseen because of the perceived gender there.

Amanda Antell: My autism diagnosis was definitely influenced by my assigned gender at birth. So, I know I’ve mentioned this on other podcasts, but for the longest time, both ADHD and autism were really only thought to have happened in young white boys.

My mom, despite taking me to three different specialists for diagnosis, they refused to, and even told her that she will grow out of it, and that I basically just have to be trained to be normal. So that just resulted in my mom really, really desperately trying to get me to understand social cues in a neurotypical setting and it just never really worked out and I’ve never been particularly good at masking so that really screwed up a lot of interactions as well. But I eventually was diagnosed at age 31 after just three sessions, telehealth sessions, so that gives you an idea of just how autistic I actually am.

Erika Donohue: I feel like I had a really different experience than a lot of people assigned female at birth. Like a lot of girls with ADHD, I had inattentive type, mainly, and a lot of inattentive type people get overlooked because they’re so quiet, a lot of them tend to do okay academically, and so, like, their struggles don’t get picked up on. When I was a really small child, I had a lot of behavioral issues. I was very disruptive. I was chatty, which is a common overlooked symptom of ADHD. But it was to such an extreme that it was impossible for my parents and teachers to ignore. That’s part of why I got my diagnosis so early. My behavior was like very extreme, especially, quote unquote, for a girl.

Amanda Antell: If I may ask, how old were you again?

Erika Donohue: How old am I?

Amanda Antell: The reason I ask is based on when you were a child in terms of what decade you were in it might have influenced your diagnostic process like I was a kid in the nineties and in the nineties it just basically unless if it was like a really extreme case, it was just thought that autism and ADHD just did not happen in girls. That was the thought process in the nineties at the time, so I was just wondering maybe that’s why, if you were born, if you were younger than me, if that had to do with that, but you don’t have to answer your age if you didn’t want to.

Erika Donohue: It could be, I’m 28, and being diagnosed at age 8, it would have been the early 2000s, like 2003.

Amanda Antell: Okay, so you would have had, okay, so the thought process even then, even though it doesn’t seem like a lot, definitely would have improved, so maybe that’s why?

Erika Donohue: Yeah, no, definitely.

Amanda Antell: And I think that’s just an interesting thing, where it’s like the thought process surrounding autism and ADHD was just so extreme between decades, where it’s like, yes. Progress, I guess, can be slow, but extreme at times, right?

Due to gender bias, it’s much harder for women to receive an autism diagnosis and even harder for trans and gender non-conforming people. Source: Image by Ryan Vail.

[00:06:26] Gender Identity and Its Influence on Experiencing ADHD

Amanda Antell: So how would you say your gender identity influences your ADHD? Do you feel like people take your condition more or less seriously because of your gender identity?

Erika Donohue: I haven’t gotten much of a sense that people take me less seriously about having ADHD because of my gender. It’s been a long time since anyone hasn’t taken me seriously about my ADHD. yeah, there’s nothing. Nothing that I can, like, specifically pick up on or point to, sometimes I can miss things like that, like sometimes I don’t pick up on sexism when it’s happening, but, yeah, not to my recollection.

Eugene Holden: I am similar. I don’t know if people are taking me more or less seriously. I don’t really pick up on that. But I think part of that is I usually am masking a lot of the time with most people, maybe except for like family and close friends, which know I’m autistic and non-binary, But I think it would, I don’t know, the two definitely influence each other because I have to unmask with my autism to be more genuinely myself. And I feel like that directly ties into my gender expression too. Those are both related methods that I have to consciously unmask or mask depending on safety levels.

Amanda Antell: So, I wouldn’t say that my autism is taken less seriously because I’m a woman. But I would say that I really have to make people acknowledge just how serious my condition can get, because I am used to functioning in neurotypical situations pretty well. So, once I do start hitting my limit, it’s pretty hard to pick up on with other people. So, when I try to explain something like driving anxiety or sleep disorders that my autism is connected to, it’s a lot harder for me to get my points across. And I also feel like even though people acknowledge my autism, they are really quick to dismiss it because I’m a woman. And it’s also just being raised as a woman and just expected to go along with other people’s expectations of you. Like, I know I’ve told this story, but when my wife and I were in Italy, there was this Italian chef that just went off at me because I wanted to put some cheese on, like, the saltiest dish ever. And, when I tell that story to my mom, and other people, it’s like, they’re like, oh, he’s Italian, he probably was just upset that you didn’t think his dish was perfect, and I’m like, I don’t care. He’s ignoring my taste, and he’s ignoring my sensory issues, and I didn’t tell him I was autistic at the time, but it’s like, I promise you, it’s one of those things where I feel like if I had he still probably would have fought me even more, so it’s just the whole people getting offended based on you voicing your needs that really annoys me with my condition sometimes, at least that’s my two cents on it.

Erika Donohue: Not really gender-related, but, in high school, I had a 504 plan, which, for people who don’t know, it’s an accommodations plan for students. I think it’s limited to like high school and earlier. I think colleges have a different system. But I had a 504-plan meeting. So, it was like my school counselor, my parents, and whatever teachers could make it who were teaching me at the time. And you don’t have a 504-plan if you don’t have a diagnosed disability. And I remember this teacher showed up, and to my face was, oh, she just doesn’t care enough. That’s why she’s struggling. And it was amazing. And terrible at the time. I look back and I just, it’s amazing. Yeah, that’s a nice name.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, that’s an example of sexism and people dismissing you based on your gender. Just so you know that.

Erika Donohue: You do think it was my gender?

Amanda Antell: Oh, big time. I promise you, if you had been a boy, I promise you that would not have happened, or at the very least, it’d be a lot less confrontational. That’s very common, actually, with women with autism and ADHD. I’m not trying to create bad memories for your bad experiences, so if you don’t feel particularly traumatized by something I’m not asking you to feel that way, but I also would say don’t dismiss things that have troubled you like that, even if you hadn’t picked up on it.

Erika Donohue: Whether I know exactly what caused them or not, it’s not that they didn’t hurt. The reason I remember it is because it felt like such a deep betrayal from someone who, while we didn’t have a one-on-one relationship, I really enjoyed his class, I liked him as a teacher. And this was one of the few times that we interacted in a more personal way. And the disrespect, the lack of care. But also, one of the symptoms of autism is sometimes missing social cues. Maybe in a different way, or to a different extent, it’s also an overlap with ADHD, and I kinda feel like my ADHD probably makes it more difficult for me to pick up on what’s sexism or not, and that’s just part of my experience.

Amanda Antell: What I would say about that is there is a lot of overlap with autism and ADHD, as we have previously talked about, but what I would also say about sexism is that it is around us everywhere in society. Both towards men and women, and especially the non-binary community, because the non-binary community is expected to adhere to binary standards even though they very clearly don’t want to or fall into that. So again, if you don’t feel like you have experienced sexism or haven’t picked up on it, I’m not asking you to create artificial memories or anything like that. But, if you look back on your memories and think something was weird or something doesn’t, isn’t right, it, there’s no harm in discussing it to get other people’s perspective on it. Like, the story you just shared with me. I would definitely say that was sexist. I guarantee you if you had been born a boy, that teacher would not have confronted you or been such an ass. And the fact that it was an older male really drives my point home as well because older men really do treat younger women like that.

Erika Donohue: Yeah, I was mainly commenting on, I agree with your assessment, and it makes perfect sense to me, and I’m just commenting on how I feel like I struggle to pick up on what is and isn’t that.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, and you don’t have to feel guilty or feel bad about that. It’s just whatever your experiences are, but if something just doesn’t seem right to you, don’t hesitate to talk about it with someone else.

The first women’s medical school opened in Pennsylvania in 1850. Photo is from 1915. Source: Legacy Center Archives, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia.

[00:12:47] Navigating the Medical Field: Experiences and Challenges

Amanda Antell: Upon receiving your ADHD diagnosis, would you say that your assigned gender at birth influences how doctors, psychiatrists, or other practitioners have treated you or still treat you?

Eugene Holden: Recently, as I’m seeking out like more information on possibly an ADHD diagnosis, my psychiatrist had me do a neurocognitive test, and she was very surprised. She was like, wow, I would not have thought you were someone who presented with ADHD symptoms, but the test showed that, and I think, just like how reserved I am. Especially when I’m masking in a doctor’s appointment or something, most of my struggles are internalized, so I don’t show them to anyone. I think that interacts with how I was raised, as an AFAB person, and how I’m perceived by doctors, even as I present more non-binary at present.

Amanda Antell: So yeah, it definitely goes back to what I said just about being born as female, and just doctors didn’t even want to consider autism as a diagnosis because they just didn’t want to go against the grain. And again, there’s that toxic mindset of not giving me a label, but the problem is it’s toxic because if I don’t have that label, I can’t get what I need.

Eugene Holden: Yeah, so I was just talking about how my psychiatrist had me take neurocognitive tests and how a lot of my struggles that present as ADHD symptoms are internalized. So just doctors don’t really see that as I present as a reserved person, even though I’m not, I think that’s related to how I was raised specifically, in the gender I was raised as.

Until 1993 most women were excluded from clinical research by law. Trans and Non-Binary people continue to be left out of most medical research. Source: Unsplash.com

Amanda Antell: It goes into the masking aspect of autism and ADHD with women. And people raised as women Because part of why it was so underdiagnosed for so long is because we’re trained to essentially act a certain way, as you know, that’s what masking is. We’re essentially forced to pretend to be normal or at least tell ourselves we’re normal. Maybe I don’t know if any of us tell ourselves we’re normal. Honestly, I feel like we’re just like accepting the fact that we have to live in pain half our life. Or at least a certain portion of our life. So that just goes back into the whole, not being taken seriously by professionals thing because it’s not just about gender identity in the medical field that women and people raised as women face. It could be about period pain and just how often that’s dismissed. It could be about migraines and just how often that’s dismissed, and just how many cases end up being something like endometritis or uterine fibroids or something like a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid that could cause like another serious medical condition. It’s just so often we’re dismissed and it’s because we’re trained to basically just stay silent, swallow our feelings. We’re basically forced to just be tough and unemotional while being perceived as overly emotional, and that just really sucks. And that’s just why I wanted to circle back to what Eugene said.

Erika Donohue: I feel like I haven’t picked up on a lot of sexism with doctors or psychiatrists or psychologists. A lot of the people who have treated me have not been men. There have been times when, like a mental health professional, I got the sense that they were making an assumption about me, but it wasn’t about my gender. It was more about my ADHD. And I felt like it came from a place. Of just not understanding what ADHD can be like for women, but not necessarily, dismissing me because of my being a woman.

Amanda Antell: What I would say about that is, again, that is a sexist situation, definitely, but that’s also medical practitioners not understanding what ADHD looks like in women versus men. And that’s very common, unfortunately, as well, and the fact that you’ve had mainly women as your practitioners or doctors, and is actually, is probably why you haven’t experienced as much sexism, because, and I’m not saying that if you have a female practitioner, it’s automatically going to be a good experience for you. Because it really isn’t. However, I would say that the sexism surrounding autism and ADHD, just the level of it you might experience or the chances of something being said or done, goes down, which is unfortunate because doctors really should just be listening to their patients regardless of gender. I would say that they definitely were making judgment calls or assumptions about you based on your gender and based on their own assumptions of ADHD. To me, that is probably what happened there, but I wasn’t there, and I’m not you, and I’m not trying to create artificial experiences for you. So, this is probably the question you actually did want to talk about.

[00:17:21] ADHD, Autism, and Gender Identity: A Deeper Dive

Amanda Antell: How would you say your ADHD intersects with your gender identity? And would you say it makes you more in touch with your gender identity or makes it more difficult? And again, we talked about this before the recording. We’re probably going to have a difference of opinion and debate here, but that does not mean either of us are wrong. We’re just going to have different positions, and that’s all.

Erika Donohue: I feel like this is a common experience for a lot of people. You know, when I was a kid, gender norms and gender stereotypes were super confusing. There were a lot of presentations of femininity that I did not get. A lot of representations of masculinity that were really exciting to me. Either I, like, felt some part of it within myself or really appreciated it. I also remember even though I had all of these differing gender norms around me, different cultural things telling me what I am and I’m not, I didn’t really care. I was certainly socialized in some traditional feminine ways, and I was treated like a girl. I learned how to get by in the world the way a girl should, most of the time. But I also just had this internal stubbornness. I knew who I was, I knew what I liked, I knew how I felt. And I didn’t really care about gender a lot. I’ve always felt comfortable enough with she/her pronouns and being referred to as a woman, and for a long time, I was just like, yeah, I’m a girl. I’m a woman. Recently I’ve thought about it more. Occasionally on the internet, I’ll hear someone talk about, like, just talk about an experience of, like, having ADHD and not picking up on social cues and expectations of you based on gender, being like, oh, why should I understand gender? I don’t even actually know. I don’t. I’m not phrasing that very well. I don’t know how to phrase that properly, but basically, I’ve encountered conversations online about how People have felt that their ADHD or other neurodivergence makes gender norms strange and alien, and difficult for them. And there are people who have tried to put words to that, tried to put words to feeling not 100 percent in a particular gender direction. And I relate to that a lot. I was really excited when I found the concept of neurogenders. Some of them I don’t get but some of them I’m like, oh, that’s very relatable. It feels comfortable enough.

Eugene Holden: I think to answer this question, I was thinking about like some childhood stuff, as well. I was raised pretty religious in a religion that reinforced the gender binary. So, growing up, that is the context I had. And as I grew up and figured out my own gender a little more, I was realizing oh, this is a social construct, and I don’t really relate to it as much, so it was simultaneously easy and hard to let go of that and accept my gender identity. I think just because being autistic, I am very much in, struggle with black and white thinking. So, I need something to be very concrete. So having a, like, what if I’m trans or non-binary question was very hard for a few years, just cause I’m the only one that can really answer that for myself. I did luckily have a helpful therapist that encouraged me. Like if I’m getting good results from going down this path, step by step, then it’s probably the path for me, even though I couldn’t see like what the end result was or what I would be perceived as after doing gender-affirming care. But I think it worked out cause I’m happy where I am now. And, yeah, my black-and-white thinking that’s directly related to autism, I know, has gotten a little less tense, so I can conceive of my own gender identity in a more outside-the-binary way, which has been helpful.

Amanda Antell: Thank you. And for me, my autism and my gender are two completely separate things. You could say they intersect in terms of how my symptoms manifest, but to me, they’re just two completely separate things, and I’ve never really thought twice about that. Even growing up, my mom, one thing I will say my mom did right by me and my sister is that she never really forced us or encouraged us to go one way or the other with gender norms. She never wanted us to be career women, she never wanted us to be homemakers, she just wanted us to explore what we were passionate about, and she just allowed us to do that in a really organic way, and that’s something that I think my mom did really well with. Growing up, I was aware I was female. I was called a girl; I’ve never really felt uncomfortable with my pronouns or my gender. I don’t really care, though, about the gender norms, I was just so indifferent to gender and gender norms that it’s, I don’t, they basically were not existent to me, I was aware of their existence, but I didn’t really care what the expectations of people were based on that, and it always was very bizarre to me that there were expectations, so I just chose to ignore it. There was like a period of middle school where I felt like I had to be as masculine as possible because I did associate femininity with being weak, but that was just due to a tough home situation I was in, but I got over that pretty quickly. I wouldn’t say it was not like other girl’s energy because it really wasn’t about attention. It was actually the opposite. I wanted people to stay away from me. So, I guess that’s my two cents on it. And in terms of your comments on the gender neurodivergence category, I would say if that’s how you are comfortable identifying, then I’ll respect that, but I consider neurodivergence and gender identity two separate things myself, but again, difference of opinion, and I will respect yours.

Erika Donohue: I feel like my mom, and even to a degree my dad, did a similar good job. They’ve just been like, oh yeah, you can do what you want, you know, which I’ve appreciated. They were like, go to college, get your degree. That was their main expectation of me. But, and a few other things. I feel like we have a lot of similarities in how we experienced gender norms as a kid. I do feel like there’s a point at which I decided I wanted to explore more nuance in my gender experience and identity. I’ve generally been like afraid of putting labels on it, and I feel like my ADHD and my gender affect each other.

Amanda Antell: Again, to me, it’s like both my autism and me being female exist within me. Again, to me, they’re just two separate things, other than like the symptom manifestation influence there. But I do agree with you that we do have very similar experiences in terms of how we treated gender norms growing up and how we were allowed to explore what we liked and didn’t like. In terms of the next question, have you ever questioned your ADHD needs due to rejection dysphoria or imposter syndrome? And would you say that you experienced either of these due to your gender identity? If so, why or why not?

Eugene Holden: I think I’ve struggled a little bit with imposter syndrome. I guess I would call it with my autistic needs just because I think it’s related to the gender I was assigned at birth and being raised as a girl, and you’re not supposed to, like, I don’t know. I was raised where I wasn’t supposed to really have needs, I guess, just like being helpful. And I think it was what was modeled for me is what I was going off of I remember, like, being more expressive as a little kid. And then at some point that just quieted, and as an adult and after getting diagnosed with autism, I’m realizing like, oh, that can resurface now. And that’s been a really good feeling to come back to myself and not be as reserved about like expressing myself and my needs and all that. I’ve noticed that’s getting a little easier as I unmask as an adult and more comfortable with my gender identity, just being able to acknowledge okay, I have needs, and that’s okay. And that can be because of, like, an autistic need, or just like something making me uncomfortable with the interaction of those identities and being able to voice that to the people around me.

Erika Donohue: I’m really glad.

Amanda Antell: Yeah. I’m happy to hear that too.

Erika Donohue: You know, it’s really funny to me at the point in life that I’m at right now, I’m like, never questioning that I have ADHD right now because life is challenging to deal with at the moment. But in those, like, pockets of time when I feel like I’m functioning really well, I’ll even think to myself, do I even have ADHD? And then, if I look closely, the answer is obviously yes, but honestly, I think it’s really funny that I even think about that. I don’t think I really question my ADHD needs because in any relation to gender, I’m thinking about the imposter syndrome part. Sometimes I do look at people with other manifestations of ADHD, and I do feel like I don’t have it as bad as them. And I think that’s part of what has contributed to me wondering if I have it. But yeah, like, everyone just presents super differently, and ultimately, we all have the core executive dysfunction, and the other core symptoms.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, I would agree with that. For me, I don’t know, rejection dysphoria? I wouldn’t say I have that; I don’t recall any times I’ve really had that. I mean, I don’t like rejection, certainly, but I accept that it’s just part of life. Imposter syndrome, I definitely have never felt that I had no trouble believing I was autistic and was actually happy I received the diagnosis upon getting it because it explained everything about my childhood and just how I reacted to situations and that I wasn’t crazy. Or I wasn’t oversensitive, and that whenever I was dismissed about having such painful experiences, it validated me, and I’m, I could confidently look back on a situation and say the other person was wrong, or they were wrong for dismissing me like that. And I’m actually pretty comfortable fighting for my autistic needs to be validated for people who really don’t understand autism, and I actually like sitting down with people and explaining what autism is, and explaining what specific needs for autistic people are, without like, using myself as an example, and trying to explain to them they need to talk to other autistic people they know to understand their needs. Really, the most difficult part about that is just explaining you can’t use me as like a universal example, you can’t use any single person with ADHD or autism as an excuse to give blanket treatment or blanket accommodation, you have to really talk to the specific people about their individual needs.

Erika Donohue: Yes.

Amanda Antell: Like, that’s actually probably the most frustrating part, that it’s like, yes, I can give you a bullet point list of autistic sensitivities and what common triggers are, that does not mean that automatically applies to the student, and I don’t want you to use that as an excuse to say you’re accommodating someone. No, I want you to actually have a conversation and do actual research and talk to actual autistic people. I always found that ironic with professors. It’s like, they are used to Assigning students all this research, these research assignments but it’s like they don’t even like to do their own research.

[00:28:42] The Intersection of Neurodivergence and Gender Norms

Amanda Antell: Are you surprised that the non-binary community has an increasing number of people being diagnosed with autism or ADHD? Why or why not, and how would you say this trend influences you?

Erika Donohue: I am not surprised. So yeah, through a lot of my childhood, like, I had periods of having friend groups, but a lot of them didn’t remain together or remain established. We kind of went our separate ways. But there was a point in my life when I found myself as part of, like, a pretty cohesive community, and we all just naturally found each other. And, as is common with a lot of neurodivergent people, we kind, we find each other. And as far as I knew, like, I was just, I don’t know, I was finding a lot of people who I just got and who got me and we enjoyed each other’s company and, I’m not gonna go into a lot of detail about this, but, yeah, like, [Sound] I felt I was having a great time meeting all these cool people and becoming friends with them, and we all liked each other. And I then gradually started finding out that pretty much all of my friends that I had just were some variation of queer, which at the time I Knew very little about and it was a whole like super important life experience for me.

Eugene Holden: I think I’m also not too surprised, and that’s based on my own personal experience. I would say most, if not all, of my friends. are some type of queer and or neurodivergent. I see that overlap in my personal life. I mean, that’s my own sample size, but it’s just like who I gravitate towards. And I don’t know, it makes a lot of sense to me in my brain of like these two things combine, just in my own experience there and the experiences of my friends.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, I’m not surprised either. And looking at these questions again, I really should have just combined 7 and 8 because my answer is just going to be, Basically, to break words, like, basically, recent research has shown that people with autism and ADHD have a higher likelihood of rejection from peers and authority, I but because we’re essentially rejected by everyone, we’re basically forced to make up our own roles to function in society, so to me, it’s not surprising at all that gender norms are being rejected as well by autistic people and people with ADHD because of, Because it’s like it’s just more rules that we don’t agree with or we’re not comfortable with. For me, the gender norms, and rules, again, I’m just so indifferent to them that it’s like, some work for me and some don’t, and I just ignore the ones that don’t. And in terms of what you said about not knowing much about like the queer community and everything, I’m trying to think of the best way to vocalize this. We’re, to me, we’re just people. It’s like, if you have questions for us, just ask.

Erika Donohue: Oh, I know. It, When I remember this experience that I had, like, I’m not here to tell that story, but it was a part of that story that Not only was I finding it’s just like I found this community, and then I went through a bunch of personal growth and yeah, that part wasn’t really important, but it was part of the experience.

Amanda Antell: To me. It’s more like people don’t have to treat the queer community as something alien. Just, if you have questions for us, just ask. I think, at least, I would prefer people ask me about my sexuality directly rather than make a lot of assumptions about me based on what they read online.

Erika Donohue: Oh yeah.

Amanda Antell: So recent research, eh, in our own experiences, has suggested that people with autism and ADHD have a higher likelihood of social rejection from peers and authority. And we essentially have to make up our own roles to survive because of that. Do you think this contributes to the growing number of non-binary people getting diagnosed with ADHD or autism?

Erika Donohue: Even if you’re not non-binary, I feel like ADHD and autism have their own, and it’s different for every person, you know, each of us have our own internal rules that come from what works well for us, what makes sense to us, and I think that those conflicts of rules they cannot fit in well with the broader general culture. I’m thinking about a particular friend of mine who has both ADHD and autism, like the way that she works, the way that things make sense to her is just so different from What she grew up with, and she had a lot of power struggles with authority throughout her life. I think the conflict of rules contributes a lot to that. I think that Nonbinary identity conflicts with a very particular set of rules that are common in broader society. So, I think the rules are, sometimes they overlap, but sometimes they’re really different.

Amanda Antell: And I’ve already answered this, but to me, it’s not surprising at all because, again, it’s like we’re being rejected by society constantly, especially in our early formative years, or at least a lot of us are. So, it makes total sense that we pick and choose or make up our own rules or just determine what rules work for us in terms of something like gender because it is a social construct, as we’ve discussed, but it’s also something very deeply rooted in genetics as well. So, to me, it makes a lot of sense. It’s actually like a yes, no, duh moment in research. To me, the way I kind of look at this trend is that neurodivergent people are really coming into their own or becoming more comfortable with themselves. And because neurodivergence itself has become more normalized throughout the years, like, just due to social media, like TikTok and stuff like that, where more and more people are seeing symptoms, or, and they’re identifying it with, identifying with it more and more, they are trying to seek out Yeah. The diagnosis is for themselves or at least assessments to see if they fit in with this. So, to me, it makes total sense that they’d also be exploring their gender more and their gender identity more, and it also just makes sense that they’re rejecting rules and constructs that don’t make sense to them. And I think I’m a pretty good example of that as well. Even if I am binary, because, again, I just take what rules work for me and society, and I reject the ones that don’t.

Erika Donohue: yeah,

Amanda Antell: So, I respect the position. So, I respect the position very well.

Pinkwashing is a common tactic for corporations to avoid accountability. Wells Fargo at San Francisco PRIDE in 1993. Source: Wells Fargo Corporate Archives.

[00:35:36] Confronting Prejudices in the Professional Mental Health Community

Amanda Antell: even with the growing acceptance of autism and ADHD in Women and people raised as women, would you say there are still a lot of prejudices in the professional mental health community towards the non-binary community or any community outside of heterosexual, cis, male, or female?

Erika Donohue: I don’t feel like I have the knowledge or the experiences to speak to this question. I’m very curious about what someone who has more experience would say, but I don’t have any,

Eugene Holden: I don’t have that direct experience. But because of things I’ve heard from friends who are also either raised as woman or non-binary or neurodivergent like me, um, I try to seek out like therapists and doctors that are specifically also trans and non-binary, or they are specializing in it just because I’ve had some dicey interactions in urgent care in the ER with doctors who aren’t, and that’s just, I’m sure there’s more prejudices out there, but there are also, I don’t know, I try to only if I can pick providers that. I know are going to understand my identities and respect them.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, I definitely feel that a little bit, like, as a cis female, I’ll say that there is still a lot of dismiss, of misogynistic dismissive attitude towards women, and again, painful periods, I’ve had those for years, but And I’ve honestly considered getting a hysterectomy just because I don’t really care that much about having kids, but the reason I haven’t had that discussion is because I’m still at the age where I could still have kids. So, I just know that I’m going to have a lot of exhausting conversations with doctors about how I could change my mind 1 day. And I just don’t feel like dealing with that. And I could just take pain pills in the meantime to during painful periods, and my wife and I, we both tried to seek out therapists or medical providers who at least have experience with dealing with autistic people. But it’s very hard considering just how. Uncommon it is for people to openly diagnose in a work industry in general, let alone medicine. So, it’s unfortunate, but even with the growing acceptance and growing trend, I don’t see this going, this problem going away anytime soon, unfortunately.

Erika Donohue: I want to second what was said about seeking out providers that share your identity. Like, having someone who just understands quickly can be a huge benefit.

Amanda Antell: Like, it goes even into social interactions in a non-medical setting where Erika, you said you tend to gravitate more towards neurodivergent crowds, and I think I’m definitely like that too, where we don’t have to explain ourselves. We have to set a specific place, certain smells, tastes, and textures set us off we have to wear I’ve met people where they have to wear sunglasses inside because fluorescent light is too much, and even without saying, openly disclosing to each other, we both know, and we’re both automatically comfortable with each other. We just, there’s just no explanation or justification is needed.

Erika Donohue: I’ll also comment that, like, I had a therapist and honestly, like, I really, really liked her. She did not seem to be neurodivergent. She had a very specific specialty that was what I needed at that particular moment. And interacting with her it was palpable, the positive regard that she had for me. She just genuinely cared about me, and then she also was fully aware that she did not know anything about ADHD, and she admitted it to me, and I feel like that is huge for someone who’s trying to be a good supportive person to someone who’s neurodivergent or just otherwise different. Just like, okay, I don’t know this. She told me like once she did what she knew she could do, she said, go find someone who can help you in this other way.

Access to mental healthcare is essential for everyone but gender bias often prevents people from getting the accurate help they need. Source: Unsplash.com.

Amanda Antell: Okay. And I’ve said this a million times, I feel like, on these podcasts, but they’re definitely, and I obviously can’t speak to the non-binary point either, but I will say that as a woman, I do still experience dismissals and prejudices from the medical community at least, and there are still a lot of assumptions made about women with autism and ADHD from professional mental health practitioners. again, we’ve had people on this podcast talk about how their symptoms were completely dismissed, even though they were pretty obviously presenting, and I’ve heard stories outside of this podcast where that’s just so common. It’s just really sad and really infuriating. That even now, we still have to fight for recognition, and I think that is becoming better over time, but it’s still going to be a long battle, and it’s just going to be a long journey before it’s completely normalized, at least on the level of the medical community, because the problem with the medical community itself, not just mental health, is the fact that it’s a lot slower to adapt to social attitudes and the growing and the evolving needs of society, whereas we’re in, when we’re in society, We’re experiencing these changes on a daily basis, so that’s just, to me, very frustrating.

Erika Donohue: Yeah, I also think that I have had, you know, being diagnosed so early, and then, having the opportunity to specifically seek out people who understand, it’s super different from my experience and super infuriating to hear that people are being dismissed when they need help.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, and I know I’ve mentioned this on the podcast too, but I met someone recently in DAS in a university where they’re essentially typecasting people with ADHD to determine whether or not they’re worthy of assessment from a professional contracted with the university.

Erika Donohue: Do you mean that they’re evaluating the symptoms of ADHD to determine?

Amanda Antell: They are basically, so basically there’s the scholarship program there where they can, where students can actually apply for coverage, or can actually get coverage for ADHD assessment specifically from an actual, from a trained professional, but the, to, But one of the stipulations is the head of DAS gets to evaluate them, quote unquote, to see if they’re ADHD enough, and this person isn’t even trained in mental health profession, isn’t even trained in mental health, let alone assessment.

Erika Donohue: That’s very terrible.

Amanda Antell: No, it is. Yeah, I don’t plan on taking that line down either.

Erika Donohue: I have had one experience, or like, this, reminded me of one experience that I’ve had. I actually volunteered. I signed up to volunteer for an ADHD medication research study once. I went to this meeting with someone and there’s this whole questionnaire of like, what are your symptoms? you know, how much are you struggling? And you know, I think it kind of makes sense, but they were like your ADHD is not to a severity that we want you as part of our research study, which on one hand, maybe I understand and another on another hand, I don’t because why wouldn’t you want to see how different kinds of ADHD respond to your drug.

Amanda Antell: Well, that’s a go again goes back to typecasting people with ADHD and the fact and I don’t know if these people were trained in mental health or not, or even trained in assessment or not, but I would bet they are not my guess. They were literally just basically they were typecasting. At least that’s what I call that. Basically, are you ADHD enough for the, for a drug program is no different than saying, are you ADHD enough to receive accommodations? Because either way, it ends up in the same result where a lot of people are dismissed and invalidated because they don’t fit this idea of what ADHD is in the, in these other people’s heads.

Erika Donohue: Yeah.

Amanda Antell: And that is, that’s one of the things that I do get angry about when talking to neurotypical people when they do have these ideas in their heads about what autism or ADHD or other conditions look like when they’re not even talking to people or even, or not taking what we’re saying seriously. Like, that’s when I actually get very combative and just basically force them to sit down and talk with me, and maybe that sounds pretty bad on here, but I basically don’t give up until I see some kind of spark in their face, in their eyes, that what they’re doing is very wrong. And that’s when I’m like, okay, I think I can probably let go now.

Erika Donohue: How, I’m trying to process this. So like, you sit down with this person. Is it kind of just like an argument, and you just argue until you see them get it?

Amanda Antell: More like what happens is it starts out as a conversation, like, recently I actually had an experience like this with someone. Basically, I’m trying to start and I’m trying to get autism assessments readily available at Oregon State for students. And I talked to someone with student fees where I did mention, my frustration and my experience talk with that person who is essentially typecasting ADHD. And they were aware of the situation. And I’m like, and you’re okay with this. And they’re like, it’s industry standard. And I’m like, if it’s industry standard to typecast people with ADHD, then that’s a serious problem and you know it.

Erika Donohue: I honestly, I don’t know what to say to that.

Amanda Antell: What I would say is be prepared for a fight if you’re getting dismissed from DAS, they eventually will give, buckle, and give a little bit. You just need to know how to fight them, and you need to know how to articulate yourself. That’s the trick with DAS.

Erika Donohue: How does that become industry standard? And I don’t expect an answer.

Elizabeth Packard pioneered rights for the mentally ill as well as women in the mid 1800s after being wrongfully committed by her husband. Source: Wiki Commons.

Amanda Antell: It actually goes back to just how autism and ADHD and other mental health conditions have been treated in general in history. We’re basically, we’ve been institutionalized, we’ve gone through electroshock therapy, I mean, not that I’ve gone through that myself, but just the history of how mental health was treated, I mean, or just how people with mental health conditions were lobotomized, it just goes back. And here’s the really scary part about situations like that, at the time, people genuinely thought they were doing both these people and society a favor by essentially trying to cure us, to cure mental health. Or locking them away where they’re, where they consider that where they might be safe, quote, unquote, where they don’t hurt themselves or others from society. So, there is this genuine thought process where essentially if we’re forced to be normal or act in or forced to function in normal settings, according on the neurotypical scale, that will become normal eventually. Like, maybe that’s overgeneralizing, maybe that’s overstating it, but I really do think that’s where a lot of these attitudes come from.

Erika Donohue: Yeah, my understanding of the history is, you know, if your symptoms are severe enough, then they, like, do something about it, but if your symptoms are small enough that you can maybe just barely get by, or you seem normally enough then you’re assumed to be normal, but like, morally deficient,

Amanda Antell: Basically.

Erika Donohue: So I also, I guess, going back to like, A lot of people are getting diagnosed with ADHD and autism recently, you know, I feel like there are like whole family cultures where you just get by, you just get through and maybe there are some Like, really good accommodations built into those cultures, maybe there’s some really toxic stuff, like some shame and some guilt, but, you know, for some people, they don’t pursue a diagnosis because It’s normal, and it’s what they’ve been surrounded by for a long time.

Amanda Antell: There’s also a lot of stigma surrounding diagnosis labels as well.

Erika Donohue: Yes, yes, so you can have like an entire family. I read what I think is a pretty beautiful story about a family of…I think most people in this family have autism, and they’ve found ways to understand themselves and support themselves and each other and, you know, like, fit into society in a way that works for them and, you know, generally seems to work for them and the people around them, and yeah, they’ve just been living without a diagnosis for a long time because the systems that they have in place to support themselves and each other have been good and, you know, maybe some of their symptoms aren’t super debilitating.

Amanda Antell: What I would say is that it works for that. I, it just. Case by case, people, if diagnosis works for some people, they should go for it, but if it doesn’t, they shouldn’t. It just totally is up to the person. In another example I’ve had that might be a little more obvious to what I said before about the industry standard comment was, I had a conversation with someone where they’re not autistic, but I had to explain to them that would be like me ignoring their disability and say and forcing them to talk with me at my mental speed and processing speed because I think I’m doing them a favor. That is, comments like that are like when you finally do get change in people when they finally recognize what they’re doing.

Erika Donohue: Yeah.

Amanda Antell: Essentially, putting the fact that they’re not being empathetic towards you into that context that they recognize is where I find where you get the most change in people.

Erika Donohue: I did have a thought. Yeah, if a diagnosis can really help if you’re from a culture that shames you for your, some of your symptoms, and then you realize, oh, I’m actually not a bad person, and you get a diagnosis, it can help a lot with that shame. And it can also, like, as long as the stigma doesn’t counteract that, and then, you know, having a diagnosis also puts you in a position to hopefully get support and have a lot of resources offered to you so that you can, maybe do more things that you didn’t think you were able to do before.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, I agree.

Judy Heumann was known as the “Mother of the Disabilities Rights Movement.” Source: Taylordw, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

[00:50:34] Final Thoughts: Respecting Neurodivergent Identities

Amanda Antell: So, for the final question, what do you want the public to know about your ADHD and how it influences your life as a person?

Erika Donohue: Yeah, nothing in particular, just like, the more that people have basic knowledge about neurodivergence and the more that they have basic knowledge of non-binary gender identity and expression, I think, and just how to be kind to people. That’s what I want people to know. If they choose to share their diagnosis with you, respect it, take it seriously. Ask them questions if needed. And then also just understand that there are intersections between gender and sexism.

Eugene Holden: I think besides like, trying to not care as much about what the public feels about my identities. I think I just hope that people can, I don’t know, believe mine and others’ experiences when they take the time to disclose them to you, because that person’s probably been dealing with that or thinking about that a long time, like I know I have with my gender identity and figuring out I was autistic. So, I guess, believe people when they tell you their experiences and also, specifically with autism, like, seek out information from autistic people and not Organizations that are not helping autistic people are not run by them because I don’t think they tend to give the best information out if they don’t have that best interest in mind.

Amanda Antell: For me just, honestly, it’s kind of what you said. For my autism, I just want people to take what I say seriously. And that what I’m experiencing is valid. And they don’t really have the right to invalidate me, either because I’m a woman or because of my autism. And it’s just about having mutual respect for each other.

Erika Donohue: Yeah. And you can’t make assumptions. You just can’t.

Amanda Antell: Thank you. And for me, it’s just what both you and Erika said, just. I don’t expect people to really be interested in autism when I disclose to them, but what I do expect them to do is to ask me if they have questions. I just don’t want them to do a Google search of autism and get to, I think, quite frankly, the same organization we’re both thinking of, Eugene. I don’t know if I’m allowed to say it on the podcast, but I’ll just say it anyways. Autism Speaks. Yeah. We don’t want people to go to that website by doing a Google search, just, I really want people to just ask us directly about our autism or ADHD, how they can actually accommodate us and what, and to me, a missing piece of that conversation is what accommodation actually looks like. Like, how do you actually accommodate someone versus what’s said in accommodation on paper? For example, just let me leave the building if there’s a fire drill. You don’t have to do anything fancy. Just let me know ahead of time. I don’t need, like, a specific place in class, but some other people might.

But that’s also why you have to ask us directly about what we need. So, thank you, Erika and Eugene, I hope you join me for another podcast.

Concluding Statements

Thank you for listening to today’s Let’s Talk Autism podcast. As you just heard, gender norms can either strongly influence a neurodivergent person or not at all. What was interesting about this conversation is how our perceptions and interactions with gender were completely different. You either had participants who tried to adhere to social norms associated to their assigned gender or people who chose to ignore them. Ultimately, each of our choices in gender expression and identity comes down to what we value. The takeaway I want the audience to have is that the gender identity is valued very differently between people but that it is a part of identity regardless. To not respect one part of an identity, no matter how major or minor it is, is disrespecting the person as a whole. Thank you for listening, and I hope you tune in for our new topic, Distance, and Distress Between Neurodivergent Communities and Mental Health Professionals.

Chrispy Jones: Thank you for listening to Let’s Talk, Portland Community College’s broadcast about disability culture. Find more information and resources concerning this episode and others at pcc.edu/dca. This episode was produced by the Let’s Talk! Podcast Collective as a collaborative effort between students, the Accessible Education and Disability Resources Department, and the PCC Multimedia Department. We air new episodes bi-weekly on our home website, our Spotify channel, and on XRAY 91.1 FM and 107.1 FM.

Special Announcement

Miguel Viveros Chavez: Welcome to Let’s Talk Collective. My name is Miguel Viveros Chavez and I’m super excited to share with you guys some very good news. We will be starting a new segment called Tech Time with Miguel. I’m super excited to have you guys here. And what is Tech Time with Miguel? So, I will be focusing on accessibility. What is accessibility? Why does it matter? We will have different episodes regarding what type of technologies and software can be used with all people with disabilities, not just blind-related, but with all disabilities, and I’m super excited to bring you guys different aspects of what items you can use on your daily lives, that you may not even have a disability, but maybe you need an application that can read items to you. One of them is called Seeing AI, which is an application for the blind that allows you to read text, see different colors, and even identify currency. We will be discussing Android apps as well and even picking out some of those apps that you guys can look up on your leisure time. Tune in and listen to all the different topics with different guests, speakers, and applications that we will be testing, having some fun discovering together. I’m super excited to have you guys come with me on this journey. Welcome to Let’s Talk Collective and thanks for always supporting us.