Sabbatical Briefing

Sabbatical (Spring 2008) Briefing To PCC Academic and Student Services All Managers

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Pam Kessinger, Librarian, Rock Creek

Duality and Paradox: “Information Literacy” in the Community College

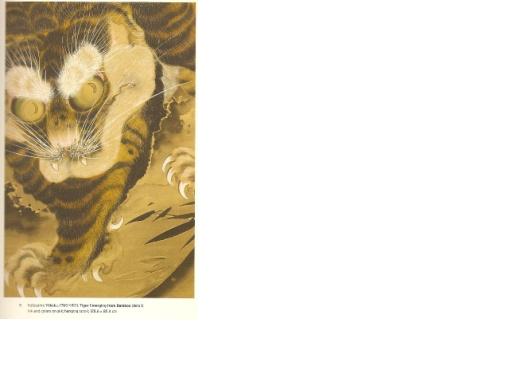

Yokoku’s painting of a tiger embodies ambiguity as well as precision.

|

|

Produced before any live tiger set foot in Japan

Yet, modeled after tiger pelts and domestic cats, it has some accuracy

Highly symbolic: representing the yin (passive, darkness, earth and water) v. the yang, the dragon (active, light, heavens, fire)

Not representational, to us, but it was frighteningly representational at the time

|

It can serve as a metaphor both for the complexity of the roles of community college librarians, and the multi-faceted concept of “information literacy”

|

Librarian roles— Keepers of books and protector of collections? Liaisons to ‘teaching’ faculty? Teachers? Student recruiters? |

Information literacy— Competencies? Skills? Measurable, assessable? Technical or intellectual (critical thinking levels)? ABE, DE, or junior-ready (Lower Division Transfer)? |

|

Study Trip Itinerary

|

|

|

May 2-4 2008, LOEX conference, Oakbrook, IL May 5, 2008, College of Dupage, Glen Ellyn, IL

|

May 7, 2008, Saint Louis Community College, Meramec Campus May 8, 2008, STLCC, Florissant Valley Campus

|

Challenges

1. A pre-college level information literacy course taught at the STLCC Meramec campus lacked enough administrative support to continue, despite the one section having a large wait-list.

2. Library managers at STLCC attend the Curriculum meetings, but do not teach, nor develop curriculum. Librarians sometimes do not receive timely updates on curricular changes, and miss opportunities to incorporate information literacy components into new or revised courses.

3. At STLCC, librarians are officially given liaison responsibility only for academic disciplines, leaving career/technical, pre-college and workforce development untouched.

4. A Vice President for Academic Affairs (i.e, campus vice-president) could not effectively change the focus of the library manager, in order to get sections of COL 020 or the new LIB 030 taught at her campus. She wanted to supervise ‘her’ campus library as a campus dean, rather than have the oversight centralized under a district position.

5. A newly appointed manager of the Gateway to College program at STLCC was experiencing some difficulty in collaborating with library faculty; she didn’t know what she was entitled to ask of the librarians.

6. Librarians were interested in responding to the GTC director’s requests, but were overwhelmed by the their unsuccessful attempts at course-integrated instruction.

7. General education requirements at STLCC now include an outcome tied to information literacy, for students to learn to “manage information.” This statement was so vague the content faculty assumed they could somehow fulfill it through their course content, without any other quantifiable measure

|

College of Dupage, Glen Ellyn, Illinois

|

Marge Peters, Professor, Reference Librarian

One of 8 full-time librarians, she oversees the third floor, College and Career Information Center. She teaches upwards of 250 instruction sessions a year. |

Innovations

1. Dupage had a large “College and Career Information Center” inside the library, with a vast collection of books and videos, as well as streaming video collections, for study skills, career development, time management, test preparation and remedial mathematics, reading, and ESOL. This was in addition to the separate Career Services Center.

2. A Dupage librarian had the single liaison area of ESL, so she maintained the department website and taught ESL-related library instruction sessions exclusively.

3. A small café inside the Dupage library shared their profits; the library in turn gave a portion to the President’s office to pay back the grant for construction. The café serves espresso; the cafeteria serves drip coffee, so there is little direct competition between the two.

4. Dupage also housed a large “Junior” (youth) materials collection, to serve the county residents outside the public library district, as a bid for building community relationships and for recruiting future students.

5. A librarian at STLCC Meramec taught one of the eight sections of COL 020 (equivalent to CG 111) each term, along with counselors, advisors, and some administrators (Campus Life director).

6. STLCC Librarians are working on developing instruction modules for LIB 101, Introduction to Library and Online Research, which was offered concurrently with the Honors Program. It is for one credit. It’s not a pre-requisite or concurrent requisite, but is “highly recommended” as part of the Capstone. It does directly articulate with nearby universities.

|

Saint Louis Community College, Meramec Campus

Becky Helbing, Assistant Professor, Reference Librarian Katy Smith, Assistant Professor, Reference Librarian Janice Hovis, Associate Professor, Reference Librarian

Katy piloted LIB 501 (will be 030, concurrent with Reading 020 or 030) |

|

All of the librarians I met with taught either instructions sessions, information literacy courses for credit, or information literacy modules within discipline courses or capstones. They were all concerned about meeting the challenge of preparing twenty-first century learners, in both the realms of information management, intellectual discernment, and new information technologies. Each was concerned about the constraints of limited resources: assessment of information literacy competencies in a longitudinal way was limited or even non-existent, and it was difficult to balance responsibilities for staffing a reference or information desk while taking time to teach or prepare for instruction.

|

STLCC, Florissant Valley Campus Sarah Perkins, Vice President, Academic Affairs Angela Brooks, Gateway to College manager

|

Cathy Riles, Reference faculty Sharon Fox, Reference faculty Susan Serns, Reading Department Chair |

Sarah Perkins asked me to facilitate a discussion between two librarians, the Reading Dept. Chair, and the newly appointed Gateway to College manager. Several issues emerged:

• A ‘scavenger hunt’ assignment used for the reading classes was not effective and students did not find it engaging.

• Librarians wanted students to learn not only how to navigate the collections, but also how to define and evaluate information. But they felt suddenly overwhelmed with requests for instruction, and worried that they lacked support for staffing the reference desk while they were away teaching.

• Angela thought that the students in the Gateway program, transitioning from mostly an unsuccessful time in high school into college, would be unprepared for college level research requirements.

Through the discussion we were able to identify that:

• Pre-college students are concrete learners, unused to ambiguity. They need initial library experiences to build a framework for scaffolding to higher level thinking and information analysis skills.

• There are identifiable, iterative competencies for information literacy, that can be scaffolded

• Library instruction could be developed for each level in this continuum, especially if the librarians and instructors would collaborate. No one person has to “do it all.”

• Additional people at the campus need to be tapped to consolidate student support (counselors that teach career development and college success, and the COL 020 sections as well as other district resources) .

I "Heart" My Library

A reductive cliché is that the "Library is The Heart of the College.” Nobody defines what that means, but it sounds and feels good. On one hand, praise is heaped on the library for being popular and fiscally responsible. On the other it has been hard for people to articulate specifically what our instructional role should be.

• Do we have enough collaboration between the library staff and student development staff?

• Is the teaching role of librarians well valued and understood?

• Is the influence of library staff and services on students’ college integration measured or promoted?

Literature Review and Reflection

Challenging and Supporting the First-Year Student: a Handbook for Improving the First Year of College

• The only writer to directly address the efficacy of librarian involvement in the First Year Experience movement was a librarian (Margit Misangyi Watts, “The Place of the Library Versus the Library as Place”, p. 339-355).

• The other chapters make the assumption that services from the library will be involved, but the connection is hardly made explicit.

• Charles Schroeder notes that there are “…longstanding and deeply embedded institutional barriers that must be overcome in order to forge effective collaborative partnerships. One of the most significant barriers is a fundamental difference in the core assumptions characteristic of academic affairs and student affairs cultures.” (p. 209)

In posting the query, “what does it mean to educate students?” to each side, Schroeder charts the differences as:

|

Faculty Focus:

Intellectual domains Cognitive development Content mastery in the discipline Acquisition of important intellectual skills |

Student Development focus:

Affective domains Practical competence Interpersonal and intrapersonal competence Leadership skills Humanitarian values p.210 |

Librarians at PCC bridge the gap between academics and students’ integrating with the college experience when we:

1. Notice whether the student can decode text or search interfaces, and adapt our instruction to their level

2. Observe whether students are able to scan, skim, or interpret a list effectively and guide their selection of sources

3. Discuss the structure of their topic, or assignment, assisting with concepts to build a search strategy

4. Liaison with their instructors for proper interpretation of the scope and purpose of their library assignments

5. Recommend appropriate courses, workshops, or campus contacts

6. Assist new students with filling out online forms (financial aid, registration, orientation)

I realized back in 2005 that while PCC was beginning to successfully address the transition to a more student-development oriented focus, it had not yet addressed information literacy, nor taken full enough advantage of the interest and talents of the librarians. Craig Kolins was interim campus president at Rock Creek at that time, and he graciously discussed with me a number of questions and ideas I was beginning to wrestle with, regarding preparing students for success. With some chagrin, he pointed out:

• He had left out any mention of libraries or information literacy from a white paper he was working on for the college, about student development.

• Furthermore, he had made the same oversight in his groundbreaking article for the Journal of Applied Research in the Community College (2001).

What librarians do

Two primary competing views of college libraries, which librarians navigate daily:

1. Student development (pre-college learning and affective skills development, e.g., ‘proper behavior’)

2. Academic, discipline-based (sometimes ‘primary’) research for sophisticated users

Keeping in mind that research arises from curiosity, which can begin with a question about a personal experience or something observed, all levels of students can pursue library assignments that are timely, keyed appropriately to their level of experience, and within the requirements of their chosen program of study.

For inexperienced searchers, Librarians teach the beginning steps of how to:

• Identify encompassing concepts

• Scan articles to identify aspects and terminology with an area of interest, to begin refining topics

• Formulate research questions

For experienced searchers, Librarians assist by:

• Defining related concepts for deeper or broader discovery

• Directing users to archival materials

• Directing users to primary sources, including people to interview

Listening and looking for other taxonomies and vocabularies

For librarians to become recognized as the purveyors of information literacy as well as the connectors district-wide for student success—the nexus of connection between SACS, departments, services and all levels of learning— requires a shift in expectations.

Librarians will initiate this shift in people’s understanding and expectations by:

1. Using alternative terms for “information literacy”, in various contexts

2. Building relationships required for collaboration

Blair Baldwin, Director of Distance Education and Professional Development, OMSI

To me science is a verb, something that people do, it’s a process. So what I see information literacy as—skepticism is a critical component of scientific inquiry, so when I see information literacy I see people having the ability to be skeptical consumers of whatever information medium they are looking at, be it the internet, or newspapers, or television, etc. To ask the question: what is the source, where did it come from, is there another way of looking at this….because that is what a scientist does when they are looking at data: they are making observations. [Emphasis mine].

Diana G. Oblinger, The Myth About Student Competency:

As more and more material is made available in digital form, IT [information technology] skills become necessary to access and manipulate those information resources. But a college/university education also implies other critical skills, such as information gathering, analysis, critical thinking, and problem solving.” (p.13) [Emphasis mine].

Oblinger et.al. offers this comprehensive definition:

Information literacy includes cognitive activities, such as acquiring, interpreting, and evaluating the quality of information. It is enabled by technical skills, such as using a computer to research, organize, analyze, and communicate. And it carries legal and ethical implications such as understanding intellectual property and copyright as well as understanding bias in the information itself.

“Googling” has become a verb, after all, but though our students are increasingly technology savvy, they are not necessarily “information literate.” For example, beyond the lazy acceptance of ‘top of search results’ without evaluation, we now need to address the issue of aggregation and echo chambers.

Brave New World of E-Hatred:

“… a decade ago, a zealot seeking to prove some absurd proposition—such as the denial of the Nazi Holocaust, or the Ukrainian famine—might spend days of research in the library looking for obscure works of propaganda. Today, digital versions of these books…are accessible in dedicated online libraries. In short, it has never been easier to propagate hatred and lies. . . . The small size of these online communities does not mean they are unimportant. The power of a nationalist message can be amplified with blogs, online maps and text messaging; and as a campaign migrates from medium to medium, fresh layers of falsehood can be created.” (p.70)

So we must work as vigorously with pre-college faculty and less-research oriented faculty in the career and technical curriculum, as well as student development faculty and staff, to address the information seeking behaviors of first-generation or underprepared students. While librarians may not always be able to call what we are teaching “information literacy” and expect to be readily understood, we can work on building relationships, piloting new efforts, and gaining partners for collaboration.

Conclusions

PCC Librarians, Library Staff and Managers are integral to the collaboration between content faculty and student development staff for developing “integration” with the college for students

Community college librarians are practitioners of applying learning theory and creating ‘learning environments’

“Information literacy” is only as polyptotonic and dismissible as ‘learning to learn’ if it is not fully understood

At the Cat Tales Zoological Park near Spokane, a visitor who asks, “Wouldn’t it be nice if I could feed a tiger,” is given the privilege of doing so. Ten raw chicken necks go for $15, and it’s easy to schedule a time with the park ranger who teaches the visitor the proper way to offer them to the big cat, and then supervises. This is a wildly creative idea that engenders interest and support for the park. Visitors are invited to “adopt” the cats, paying for their ongoing care.

Applying the same framework for creative solutions (c.f. Ofstein), PCC should ask:

Wouldn’t It Be Nice If PCC developed a seamless pathway for students to become information literate from high school and Gateway to College levels, into Lower Division Transfer, or Career and Technical courses; from ESOL, ABE, DE to college level courses; from admission to junior-ready transfer. . . and see what kinds of opportunities arise. *

Bibliography

Albin, Tami, et al. "Meeting the Student Learning Imperative: Building Powerful Partnerships between Academic Libraries and Student Services." American College and Research Libraries Bi-Annual Conference. Minneapolis, April 7-10 2005.

Baldwin, Blair. Oregon Museum of Science and Industry. Interview. August 14, 2008.

"Brave New World of E-Hatred." The Economist 388:8590 (2008): 69-70.

Challenging and Supporting the First-Year Student: A Handbook for Improving the First Year of College. Ed. M. Lee Upcraft and John N. Gardner. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2005.

Falk, John H., and Beverly K. Sheppard. Thriving in the Knowledge Age: New Business Models for Museums and Other

Cultural Institutions. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2006.

Hu, Shouping, et al. Reinventing Undergraduate Education: Engaging College Students in Research and Creative Activities. Vol. 33. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publications, 2008.

Kolins, Craig. "An Appraisal of Collaboration: Community Colleges as Vanguards." Journal of Applied Research in the Community College 9.1 (2001): 45-56.

Oblinger, Diana G., and Brian Hawkins. "The Myth about Student Competency: Our Students Are Technologically Competent." Educause Review 41.2 (2006): 12-3.

Ofstein, Lauren. "Creative Approaches to Collaboration." LOEX Annual Conference. Oakbrook, IL, May 1-3 2008.

Poole, Carolyn E. "A Missing Link: Counselor and Librarian Collaboration." Community & Junior College Journal 11.4 (2003): 35-43.

Yokoku, Katayama. "Tiger Emerging from Bamboo (Detail). " Untamed Beauty: Tigers in Japanese Art. Ed. Minneapolis Institute of Art. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2005. 19.

* And the person feeding a tiger is….?