Social Justice & The Irish Perspective

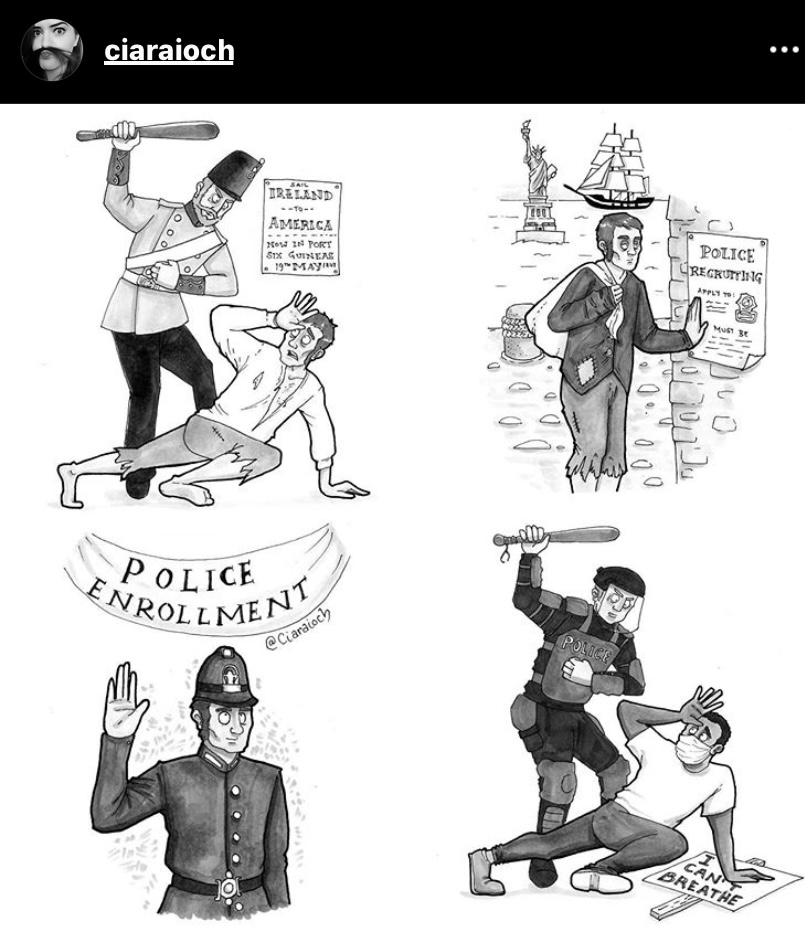

The Instagram post above (@ciaraoich) is so painfully accurate that I was compelled to create a blog post to elaborate on the narrative it depicts. Prepare yourselves for a fire-hose-of-information-to-the-face moment, folks.

The establishment of prohibitive penal laws in the early 17th century by the English government restricted Irish Catholics’ participation in virtually every facet of public life. These codes were implemented in an attempt to consolidate land ownership and therefore exert ever increasing control over Ireland by dissuading the native Irish from their Catholic faith and aligning them with the Church of England. The government also sought in the process to create an upstanding English citizenry out of the Irish peasantry, whom they felt were unruly and barbaric. This affected the majority of the population of Ireland to such a degree that Irish language and cultural practices were quite often limited almost exclusively to very private sectors within the home and immediate community while English increasingly became the dominant language in public spheres. In the mid-19th century a blight introduced from North America destroyed Ireland’s potato crop—an inexpensive but nutritious food source on which the vast majority of Ireland was reliant. As a result of the abject poverty created by penal laws, a catastrophic loss of life occurred due to starvation, exposure, and disease. This caused a major out migration of Irish people to North America and remains the main historical context for many Americans’ ‘Irish’ identity.

Prior to the arrival of the ‘Famine Irish,’ many Irish already living in the US faced similar discriminatory practices by the dominant White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) establishment. This was a continuation of the colonial practices of Europe, which utilized ‘racialization’ as a way to categorically deny equal rights to non-white communities. As a result, bigoted attitudes sparked the era of ‘No Irish Need Apply,’ and forced these traumatized immigrants into paralleled socio-economic situations as disenfranchised Black Americans—enslaved and free. Due to this shared experience many Irish and Black Americans lived in the same neighborhoods, sometimes intermarried, and routinely worked side by side in the same jobs. In fact, these two communities were often portrayed similarly even within popular media such as in early Tin Pan Alley and later Vaudeville forms of entertainment. Along with the stock stage personas of Jim Crow and Jim Dandy, there arose the Irish characters of Paddy and Bridget—stereotypes that soon became the objects of scorn and ridicule by mainstream America. Racialized characters also begin to materialize in newspapers and even in high society publications such as Harper’s Bizarre, which sought to dehumanize the Irish so as to justify denying them basic rights and considerations.

The expectation persisted in the US that Irish immigrant and Black communities would continue to cohabitate in the lowest margins of the socio-economic hierarchy of American Capitalism. However, prior to the Civil War and with the arrival of immigrants from famine-stricken Ireland, which caused an increase in anti-Irish sentiments, greater acceptance became central to the plight of the Irish in America. As a result, they shouldered their way into the white polity of the country through infiltrating the Democratic Party, early labor unions, and the Catholic church, while utilizing forms of urban social disorder—race riots and policing, for example—to distance themselves from and antagonize Black communities. In particular, as a way to thwart policing of their own communities that dealt with high amounts of domestic and neighborhood violence (referred to as the ‘Irish Problem’), the Irish enlisted in law enforcement in large numbers, often rising within and holding the highest ranks of office. The management and implementation of this expansive agenda of acceptance by WASP society through the subjugation of Black America inevitably merited them admission into White America but at a grave cost.

Prior to the Civil War, famed Irish political figure Daniel O’Connell—’the Liberator’—was vying for Catholic emancipation in Ireland and gaining a large following among the masses in support of his Catholic Association. Not without his own flaws but an abolitionist and native Irish speaker all the same, O’Connell was frustrated by the position of many of his fellow countrymen now residing in the United States toward slavery and the Black community. On May 9th, 1843 (two years before the onset of the famine) at a meeting of the Loyal National Repeal Association in Dublin, Daniel O’Connell admonished Irish Americans: “Over the broad Atlantic I pour forth my voice, saying, come out of such a land, you Irishmen; or, if you remain, and dare countenance the system of slavery that is supported there, we will recognize you as Irishmen no longer.” His call went unanswered.

Many Irish-Americans believe that their forebearers were a hard-working people who fled persecution by the English government and through the virtuous America ‘melting pot’ gained a foothold in the US fairly and by merit. While this is true in many respects, it is not without erasure of violence toward Black communities and a resultant loss of identity. Most concepts of Irish identity in 20th century America reflected a kitsch nostalgia echoed through traditions surrounding St. Patrick’s Day, Catholicism, or fascination with stereotypes established by early forms of American entertainment. However, what often is omitted and rarely challenged is that these manifestations of Irishness in fact were the few cultural tokens allowed by greater White society to persist. In a rush to achieve acceptance, most of what truly made the Irish unique—their history, culture, stories, songs, and language—was lost. The inescapable conclusion of this historical narrative is regardless of the social movements that championed the rights of the Irish in America, hatred and subjugation of Black people was the critical element necessary to gain social acceptance or at the very least tolerance in the United States.

The tragedy of the Irish experience is twofold. They faced a continual erosion of sovereignty by the English government through colonization and penal codes in Ireland that lead to the death and expulsion by forced emigration of two and a half million native Irish by famine. As they arrived on the shores of North America, traumatized by the journey and the memory of their oppression, they were faced with similar exploitation and bigotry as in Ireland. In an intense desire to escape newfound hatred and pervasive poverty, the vast majority of Irish America chose not to heed the call of Daniel O’Connell to forsake the attitudes of WASP society toward Black Americans but rather to adopt the manners and attitudes of American Empire to gain acceptance by White society that saw the near erasure of their deeper cultural identity as a result.

We are, once again, at a crossroads in society where Daniel O’Connell’s ‘call’ is as ever relevant as it was when he made it 177 years ago. Whether you identify as Irish, of the Irish diaspora, or simply hold an affinity for Ireland—it’s imperative that you understand that to remain silent in the face of racism, bigotry, and a police system that kills with impunity is to relegate yourself to whiteness. As O’Connell—the great Catholic Emancipator of Ireland— stated quite clearly, “we will recognize you as Irishmen no longer!“

Resources to explore:

The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class by David R. Roediger

Race in Modern Irish Literature and Culture by John Brannigan

After Optimism? Ireland, Racism and Globalisation by Ronit Lentin

Toward a Global Idea of Race by Denise Ferreira da Silva