The Origins of All Martial Arts Started in Northern India with Buddhist Monks & Yoga

Yoga Life: The origin of martial arts in yoga

Originally published in The Daily Star by Dr. Ashok Kumar Malhotra Updated May 25, 2018 a Nobel Peace Prize nominee. He is Emeritus SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of Philosophy and founder of the Yoga and Meditation Society at the State University College at Oneonta, New York.

Martial arts originated on the Silk Road when Buddhist monks traveled from India to China from approximately 200 B.C.E. to 1450 C.E. during this time the Silk Road was a network of trading routes, involving the passing of goods to people from city to city. Since the Chinese emperors fell in love with the Buddhist teachings of nonviolence, meditation and yoga, they wanted to have these teachings brought to China from India. A number of scholar-monks from China were sent to India to learn and write down these teachings of the Buddha. Their massive books were brought to China through the Silk Road.

Martial arts originated on the Silk Road when Buddhist monks traveled from India to China from approximately 200 B.C.E. to 1450 C.E. during this time the Silk Road was a network of trading routes, involving the passing of goods to people from city to city. Since the Chinese emperors fell in love with the Buddhist teachings of nonviolence, meditation and yoga, they wanted to have these teachings brought to China from India. A number of scholar-monks from China were sent to India to learn and write down these teachings of the Buddha. Their massive books were brought to China through the Silk Road.

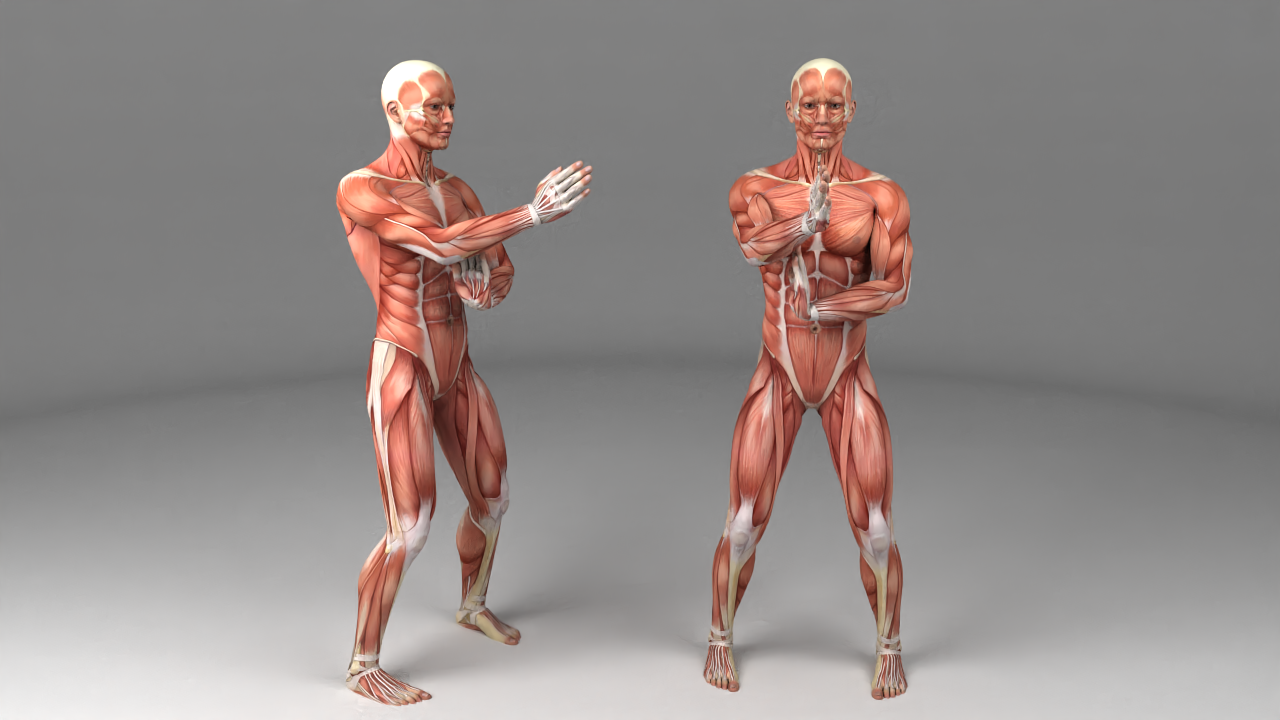

The monks packed these sacred books on the backs of their donkeys and mules, undertaking this long and arduous journey for months. While traveling, these monks were attacked by thieves who mistook the laden animals for carrying gold and silver. The monks, who practiced total non-violence, did not want to retaliate by hurting their attackers. Since they had mastered the art of yoga and meditation, they could summon up their total energy through any single part of their bodies. When attacked, they concentrated that power in a finger, hand, foot or elbow like a laser beam to stop the attacker without injuring him.

If the attacker was rushing at him with full force, the monk would use the swift motion of his hands and arms by helping the attacker to fall on his face through his own body weight (Judo) or to halt his blow through the monk’s empty hand (Kora Hath in Sanskrit, or Karate) or stop him through the use of an arm or elbow or foot. This led to the innovation of diverse techniques leading to the creation of such martial arts as judo, karate, kung fu, tai chi and others. Of course, under the hands of various masters, they were further modified and developed into unique martial arts practiced by the royalty and their protectors. Non-violence as their creed, the monks used the technique of yoga to protect themselves and their attackers from any injury thus giving the world various martial arts.

5 Superhuman Skills Martial Arts Can Subconsciously Have on Your Brain – Scientists look to the effects of specific forms of exercise.

Originally published on The Conversation March 29, 2019 by Ashleigh Johnstone, PhD Researcher in Cognitive Neuroscience, Bangor University, UK.

We are all aware that exercise generally has many benefits, such as improving physical fitness and strength. But what do we know about the effects of specific types of exercise? Researchers have already shown that jogging can increase life expectancy, for example, while yoga makes us happy. However, there is one activity that goes beyond enhancing physical and mental health; martial arts can boost your brain’s cognition, too.

- Improved Attention – Researchers say that there are two ways to improve attention, through attention training (AT) and attention state training (AST). AT is based on practicing a specific skill and getting better at that skill, but not others — using a brain training video game, for example. AST on the other hand is about getting into a specific state of mind that allows a stronger focus. This can be done by using exercise, meditation, or yoga, among other things. It has been suggested that martial arts is a form of AST, and supporting this, recent research has shown a link between practice and improved alertness. Backing this idea up further, another study showed that martial arts practice — specifically karate — is linked with better performance on a divided attention task. This is an assignment in which the person has to keep two rules in mind and respond to signals based on whether they are auditory or visual.

- Reduced Aggression – In a US study, children aged 8-11 were tasked with traditional martial arts training that focused on respecting other people and defending themselves as part of an anti-bullying program. The children were also taught how to maintain a level of self-control in heated situations. The researchers found that the martial arts training reduced the level of aggressive behavior in boys, and found that they were more likely to step in and help someone who was being bullied than before they took part in the training. Significant changes were not found in the girls’ behavior, potentially because they showed much lower levels of physical aggression before the training than the boys did. Interestingly, this anti-aggression effect is not limited to young children. A different piece of research found reduced physical and verbal aggression, as well as hostility, in adolescents who practiced martial arts, too.

- Greater Stress Management – Some forms of martial arts, such as tai chi, place great emphasis on controlled breathing and meditation. These were strongly linked in one study with reduced feelings of stress, as well as being better able to manage stress when it is present in young to middle-aged adults. This effect has also been found in older adults — the 330 participants in this research had a mean age of 73 —too. And the softer, flowing movements make it an ideal, low-impact exercise for older people.

- Enhanced Emotional Well-Being – As several scientists are now looking into the links between emotional well-being and physical health, it’s vital to note that martial arts has been shown to improve a person’s emotional well-being, too. In the study linked above, 45 older adults (aged 67-93) were asked to take part in karate training, cognitive training, or non-martial arts physical training for three to six months. The older adults in the karate training showed lower levels of depression after the training period than both other groups, perhaps due to its meditative aspect. It was also reported that these adults showed a greater level of self-esteem after the training, too.

- Improved Memory – After comparing a sedentary control group to a group of people doing karate, Italian researchers found that taking part in karate can improve a person’s working memory. They used a test that involved recalling and repeating a series of numbers, both in the correct order and backwards, which increased in difficulty until the participant was unable to continue. The karate group were much better at this task than the control group, meaning they could recall longer series of numbers. Another project found similar results while comparing tai chi practice with “Western exercise” —strength, endurance, and resistance training. Evidently, there is far more to martial arts than its traditional roles. Though they have been practiced for self-defense and spiritual development for many hundreds of years, only relatively recently have researchers had the methods to assess the true extent of how this practice affects the brain. There are a such a huge range of martial arts, some more gentle and meditative, others combative and physically intensive. But this only means that there is a type for everyone, so why not give it a go and see how you can boost your own brain using the ancient practices of martial arts.

The Yoga of Combat by Baron Baptiste and Kathleen Finn Mendola

August 28th 2007 originally published in Yoga Journal – Baron Baptiste is a yoga teacher and athletic trainer in Cambridge, Massachusetts, known for his work with the Philadelphia Eagles and as the host of ESPN’s “Cyberfit.” Kathleen Finn Mendola is a writer based in Portland, Oregon.

Yoga and aikido share the goal of a tension-free body that uses energy wisely and efficiently. In sixth-century China, because Zen Buddhist monks who meditated for long hours were developing spiritually but weakening physically, Prince Bodhidharma introduced monks at the Shaolin Temple to what later became known as kung fu a martial art based on Indian yoga. The monks were not only priests but warriors too, and practiced this first martial art on a daily basis.

In the seventeenth century, Okinawa (an island between China and Japan) was captured by the Japanese, who took away the islanders’ weapons. To defend themselves, the Okinawans turned to the martial arts of China. As the century progressed, the martial arts slowly transformed from a means of combat to a spiritual path. Both yoga and martial arts are modes of self-healing that aim to dissolve stress and increase awareness. Both practices strive to awaken energy, or chi, within the body. Like yogis, martial arts practitioners learn how not to think, how to go beyond thinking to samadhi, a state of meditative union with the Absolute. Aikido, one of the newer forms of martial arts, embodies principles remarkably similar to the yoga tenets of moving from the body’s center, relaxing under pressure, and extending chi.

The Zen-like principles of aikido de-emphasize the power of the intellect, instill intuitive action, and help individuals overcome the effects of evaluating, judging, analyzing, thinking overriding conditions of our society. Yoga too encourages surrender, letting the mind go, and being in the present, and downplays striving and pushing.

“Competition is an integral part of life in our culture, starting from birth,” says George Leonard, who holds a fifth-degree black belt in aikido, co-owns an aikido studio in Mill Valley, California, and is author of several books including The Way of Aikido: Life Lessons from an American Sensei (Dutton, 1999). But progress in aikido comes with patient and diligent training. He tells his students “to stay with the process, enjoy this level, do not strive; keep practicing and don’t try to get anywhere.”

Yoga Mat as Dojo

A dojo the Japanese word for a place of enlightenment is a temple of sorts, and the place where martial artists practice. In the dojo, you make contact with your fears, reactions, and habits. This arena of confined conflict, with an opponent or partner engaging you, helps you to understand yourself more fully. Though in yoga the process is more individual, your yoga mat can be a dojo. Poses can take you deep inside yourself, challenging you to loosen the grip of indiscriminate emotions such as anger or fear.

The ultimate aim of aikido is to free the individual from anger and illusion, fear and anxiety. This is done by constantly having to become nonaggressive, according to Leonard. Aikido moves protect both the attacked, and if possible, the attacker. An aikidoist usually chooses not to harm an attacker even though the opportunity to harm is present. “Each time you’re forced to be nonaggressive, you’re brought nose to nose with your internal aggression,” Leonard says. “This isn’t done by denial but by integrating the emotion, understanding it, and transforming it into something else which, ultimately, is love.”

A parallel exists in yoga as practitioners confront their own emotions. When working through poses, people often stumble upon anger, fears, judgments, and vulnerabilities. This detritus can manifest in different body parts. For example, feelings of grief are often lodged in the chest, while fear and anger reside in the hip area. The spine, the back of the body, can represent returning to the past, making backbends challenging for many. And inversions can bring about a sense of vulnerability. Working through emotions these poses evoke is part of the practice.

Yoga and aikido mesh not only philosophically but in a physical sense as well both are nonlinear activities. Aikido and yoga practitioners are less likely to suffer from repetitive stress injuries that they may incur from linear sports such as running and bicycling.

The circular, flowing nature of aikido encourages entire body movement. That’s not to say that a martial artist isn’t in need of what Leonard refers to as the “optimal muscle tone” that yoga offers. “Flexibility is essential as rigidity can cause accidents,” he says. For example, the shoulders can suffer a lot of damage when diagonal rolls are performed. This standard aikido move involves gracefully rolling from the right hand, arm, and shoulder across the back to the left buttock and leg. “Done correctly,” says Leonard, “it’s magical.” Performed incorrectly, rolls can injure the shoulder and possibly break the collarbone. In this case, the supple flexibility that yoga cultivates becomes absolutely vital.

High kicks and harsh, staccato movements are the Hollywood version of many martial arts, yet such kicks are considered a waste of energy as they’re not an efficient method of thwarting an opponent, according to Leonard. Nonetheless, kicking at a more moderate level is inherent in the martial arts and aikido is no exception. Twisting and exerting power from the lower limbs involves the long muscles of the body—thighs, buttocks, abdomen, and back—which all attach to the pelvic girdle. To develop the flexible hip area and strong lower body essential to an aikidoist, practice hip-opening yoga postures such as Eka Pada Rajakapotasana (Pigeon Pose) and all standing poses, which develop leg strength.

The kicking and falling required of an aikidoist can be rough on the knees. Though the tissue surrounding the knees (the meniscus) wears down after repetitive use in any sport, as long as the knee socket is snugly supported by the tendons and continually strengthened, the knees can support the movements of aikido. For knee strengthening and toning, practice Virasana (Hero Pose).

Yoga and aikido share the goal of a tension-free body that uses energy wisely and efficiently. “If one set of muscles is tense, then they’re firing and taking energy away from other parts of the body,” Leonard says. “In aikido, you must be able to relax every muscle except the one being used. It can be mind-blowing, being very relaxed but able to exert enough to bring someone down to the ground.” In the best of yoga, the same thing happens, adds Leonard. “Out of relaxation comes power.”

Budokon, made in America, mixes yoga with martial arts

Originally published in Reuters, New York by Dorene Internicola, December 24th 2012

Budokon, a workout program developed in 21st century America, blends the ancient mind-body practices of yoga and martial arts into a program that aims to reward followers with conditioning, mindful meditation and progressively colored karate-type belts.

“Budokon is a yoga, martial arts and meditation trifecta,” said Mimi Rieger, who teaches the not-so-ancient practice in gyms, studios and workshops in the Washington, DC area. An instructor in the 3,000-year-old practice of yoga since 2003, Rieger, founder of Pure Fitness DC, is one of approximately 400 teachers worldwide who are trained in Budokon, which did not exist before 2002.

Although mainly done in the United States, Rieger said she will teach Budokon in Turkey, Denmark and Sweden next year and workshops are also scheduled in London, Germany, Korea and Japan. She says the hybrid offers the student an intense, full-body workout as it blends the integrity of the martial arts movement with the fluidity of yoga.

“It’s like a beautiful symphony of the two,” said Rieger, who is among the first women to get a brown belt in the Budokon sequence of six belts: white, red, blue, purple, brown and black. Budokon, which is Japanese for “the way of the warrior spirit,” began in 2000 as the brainchild of Cameron Shayne, a martial arts expert and yoga enthusiast originally from Charlotte, North Carolina, looking to solve a dilemma faced in his own practice.

“Through martial arts I experienced meditation; both yoga and martial arts share self-reflection, but both suffered from the same disease of being stripped down to a westernized workout,” said Shayne, founder of Budokon University in Miami, Florida. A typical Budokon session begins with 20 minutes of yoga sun salutations to, as Shayne says, “lighten and open the body,” followed by a martial arts segment of explosive, dance-like movement. The end is a guided meditation.

“There is no breath count; we don’t stop,” said Shayne, who describes the movements as snakelike. Observers will note echoes of Tai Chi. “Modern yoga can be very angular. Our primary series is a circular, continuous transition practice,” he explained.

Adam Sedlack, senior vice president of UFC (Ultimate Fighting Championship) Gym, a national chain of family fitness centers specializing in mixed martial arts training, believes the novice should begin with a specific practice before tackling hybrids like Budokon.

“It’s more efficient to take a karate class, then a yoga class, and then a tai chi class than it is to combine them,” Sedlack said, “so the individual can focus on individual skill sets. The beautiful thing about mixed martial arts is that you’re learning a skill while you’re working out and burning calories.” He notes that martial arts is as much about the confidence of walking down the street with your head up high as it is about learning to kick and hit.

Richard Cotton, of the American College of Sports Medicine, said Budokon can offer a challenging change for people with more advanced levels of fitness. “If you’re a yoga or tai chi purist, it (Budokon) is not that, but it is variety, and variety is rarely a problem,” he said. He points out that one needn’t do Budokon, or yoga or Pilates to have a so-called mind-body experience.

“Running strength training, and certainly golf, can be a mind-body experience if you’re staying in touch with your body,” he said. “You can have a mind-body walk.” A few years ago, Shayne began offering a separate Budokon yoga practice because some people found the martial arts aspect of his practice intimidating or confrontational.

“It became a necessity to give that audience what it was asking for,” he explained. People either love Budokon, he added, or they hate it and that’s fine with him. “I don’t need a million people doing Budokon. I don’t need someone who walks into class looking for a quick fix,” he said. “I need people who feel it as an

Contact Information

Preferred Emails: Moses.Goldfeld@pcc.edu; and Moses3@pdx.edu

Websites

Namaste’ from Moses

“We as teachers and lifelong learners must continually improve each other’s understanding that both teacher and adult learner alike, that regardless of our prior education, experience, certification, licensing or authority, that none of us can accurately predict the exact level of success that any learner’s efforts, strategies, methodologies, philosophies or behavioral choices may produce” – Moses Goldfeld